3.”HEY, MAN, I JUST SHOT A WOMAN.”

Waiting in Jalalabad, the teams were getting feedback from Washington. Gates didn’t want to do this, Hillary didn’t want to do that. The Shooter still thought, We’d train, spin up, then spin down. They’d eventually tank the op and just bomb it.

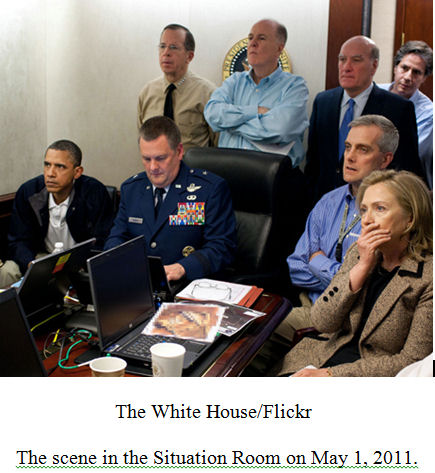

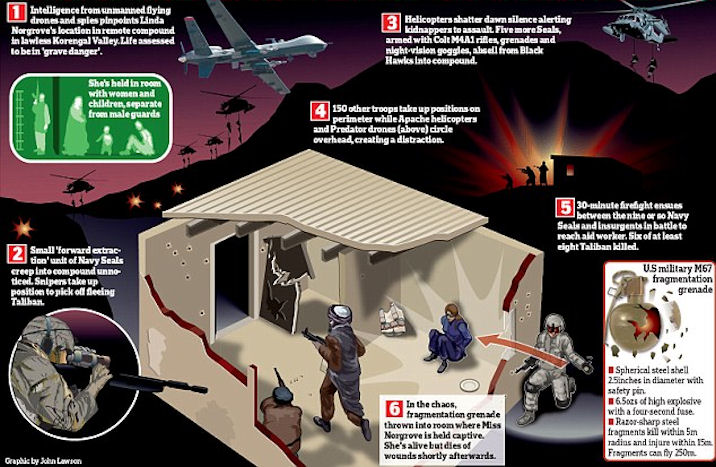

But then the word came to Vice Admiral William McRaven, head of Joint Special Operations Command. The mission was on, originally for April 30, the night of the White House Correspondents’ dinner in Washington.

McRaven figured it would look bad if all sorts of officials got up and left the dinner in front of the press. So he came up with a cover story about the weather so we could launch on Sunday, May 1, instead.

There was one last briefing and an awesome speech from McRaven comparing the looming raid and its fighters to the movie Hoosiers.

Then they’re gathered by a fire pit, suiting up. Just before he got on the chopper to leave for Abbottabad, the Shooter called his dad. I didn’t know where he was, but I found out later he was in a Walmart parking lot. I said, “Hey, it’s time to go to work,” and I’m thinking, I’m calling for the last time. I thought there was a good chance of dying.

He knew something significant was up, though he didn’t know what. The Shooter could hear him start to tear up. He told me later that he sat in his pickup in that parking lot for an hour and couldn’t get out of the car.

The Red Team and members of the other squad hugged one another instead of the usual handshakes before they boarded their separate aircraft. The hangars had huge stadium lights pointing outward so no one from the outside could see what was going on.

I took one last piss on the bushes.

Ninety minutes in the chopper to get from Jalalabad to Abbottabad. The Shooter noted when the bird turned right, into Pakistani airspace.

I was sitting next to the commanding officer, and he’s relaying everything to McRaven.

I was counting back and forth to a thousand to pass the time. It’s a long flight, but we brought these collapsible camping chairs, so we’re not uncomfortable. But it’s getting old and you’re ready to go and you don’t want your legs falling asleep.

Every fifteen minutes they’d tell us we hadn’t been painted [made by Pakistani radar]. I remember banking to the south, which meant we were getting ready to hit. We had about another fifteen minutes. Instead of counting, for some reason I said to myself the George Bush 9/11 quote: Freedom itself was attacked this morning by a faceless coward, and freedom will be defended. I could just hear his voice, and that was neat. I started saying it again and again to myself. Then I started to get pumped up. I’m like: This is so on.

I was concerned for the two [MH-47 Chinook] big-boat choppers crossing the Pakistani border forty-five minutes after we did, both full of my guys from the other squadron, the backup and extraction group. The 47’s have some awesome antiradar shit on them, too. But it’s sti

e it, they can send a jet in to shoot them down. Flying in, we were all just sort of in our own world. My biggest concern was having to piss really bad and then having to get off in a fight needing to pee. We actually had these things made for us, like a combination collapsible dog bowl and diaper. I still have mine; I never used it. I used one of my water bottles instead. I forgot until later that when I shot bin Laden in the face, I had a bottle of piss in my pocket.

I would have pissed my pants rather than trying to fight with a full bladder.

ll a school bus flying into a sovereign nation. If the Pakistanis don’t lik

Above the compound, the Shooter could hear only his helo pilot in the flight noise. “Dash 1 going around” meant the other chopper was circling back around. I thought they’d taken fire and were just moving. I didn’t realize they crashed right then. But our pilot did. He put our five perimeter guys out, went up, and went right back down outside the compound, so we knew something was wrong. We weren’t sure what the fuck it was.

We opened the doors, and I looked out.

The area looked different than where we trained because we’re in Pakistan now. There are the lights, the city. There’s a golf course. And we’re, This is some serious Navy SEAL shit we’re going to do. This is so badass. My foot hit the ground and I was still running [the Bush quote] in my head. I don’t care if I die right now. This is so awesome. There was concern, but no fear.

I was carrying a big-ass sledgehammer to blow through a wall if we had to. There was a gate on the northeast corner and we went right to that. We put a breaching charge on it, clacked it, and the door peeled like a tin can. But it was a fake gate with a wall behind it. That was good, because we knew that someone was defending themselves. There’s something good here.

We walked down the main long wall to get to the driveway to breach the door there. We were about to blow that next door on the north end when one of the guys from the bird that crashed came around the other side and opened it.

So we were moving down the driveway and I looked to the left. The compound was exactly the same. The mock-up had been dead-on. To actually be there and see the house with the three stories, the blacked-out windows, high walls, and barbed wire – and I’m actually in that security driveway with the carport, just like the satellite photos. I was like, This is really cool I’m here.

While we were in the carport, I heard gunfire from two different places nearby. In one flurry, a SEAL shot Abrar al-Kuwaiti, the brother of bin Laden’s courier, and his wife, Bushra. One of our guys involved told me, “Jesus, these women are jumping in front of these guys. They’re trying to martyr themselves. Another sign that this is a serious place. Even if bin Laden isn’t here, someone important is.”

We crossed to the south side of the main building. There the Shooter ran into another team member, who told him, “Hey, man, I just shot a woman.” He was worried. I told him not to be. “We should be thinking about the mission, not about going to jail.”

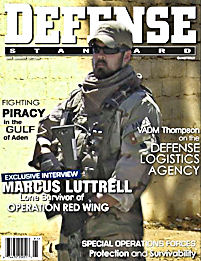

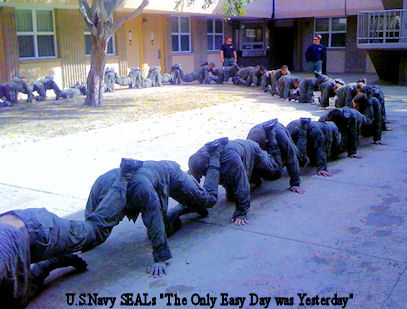

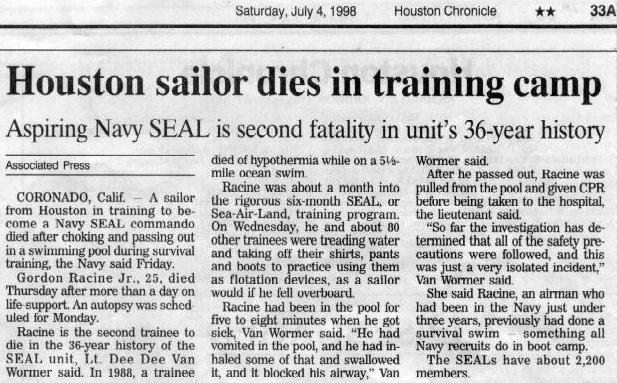

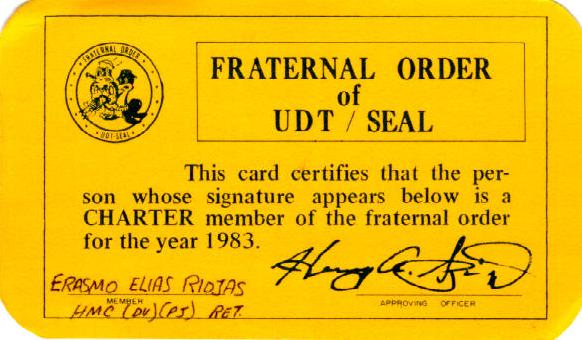

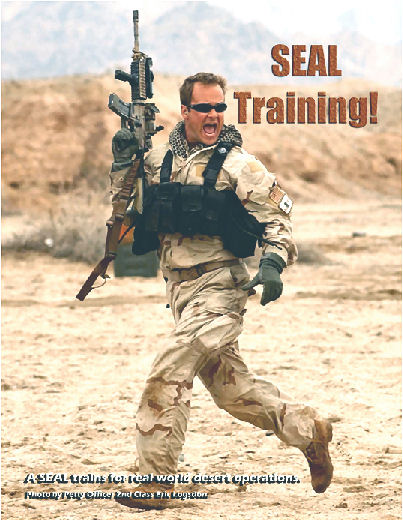

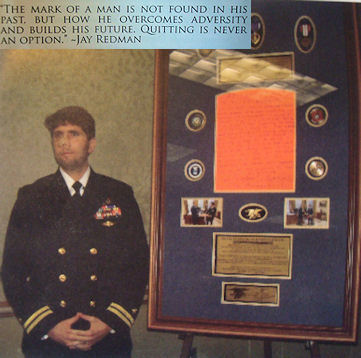

For the Shooter personally, bin Laden was one bookend in a black-ops career that was coming to an end. But the road to Abbottabad was long, starting with the guys who tried and failed to make it into the SEALs in the first place. Up to 80 percent of applicants wash out, and some almost die trying.

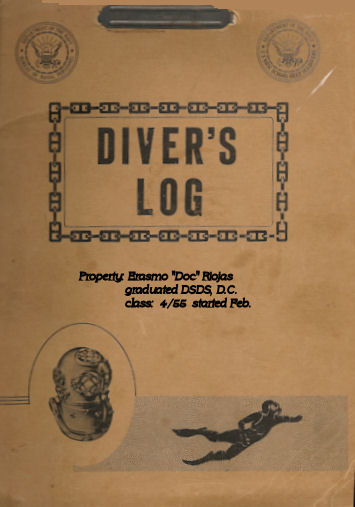

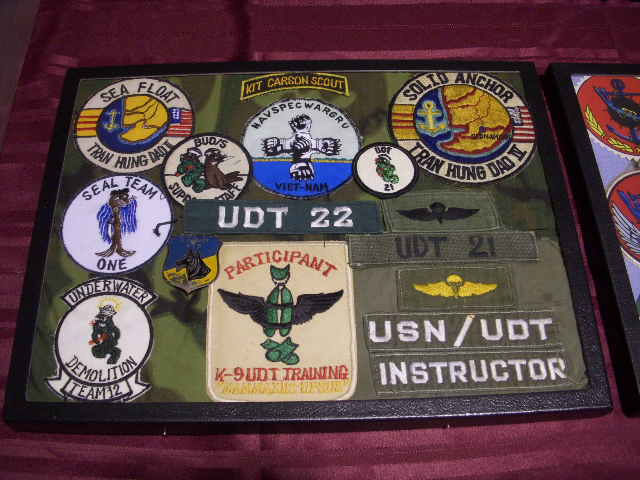

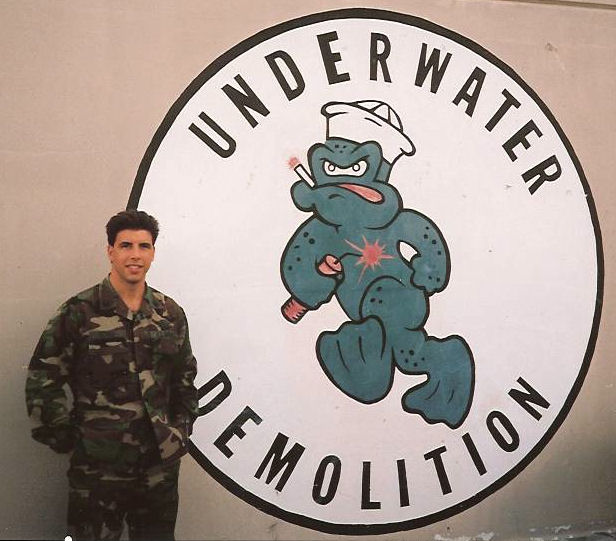

In fact, during the Shooter’s Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training in the mid-nineties, the torture-chamber menu of physical and emotional resistance and resolve required to get into the SEALs, there was actually a death and resurrection.

“One of the tests is they make you dive to the bottom of a pool and tie five knots,” the Shooter says. “One guy got to the fifth knot and blacked out underwater. We pulled him up and he was, like, dead. They made the class face the fence while they tried to resuscitate him. The first words as he spit out water were ‘Did I pass? Did I tie the fifth knot?’ The instructor told him, ‘We didn’t want to find out if you could tie the knots, you asshole, we wanted to know how hard you’d push yourself. You killed yourself. You passed.'” “

I’ve been drown-proofed once, and it does suck,” the Shooter says.

Then there is Green Team, the lead-heavy door of entry for SEAL Team 6. Half of the men who are already hardened SEALs don’t make it through. “They get in your mind and make you think fast and make decisions during high stress.”

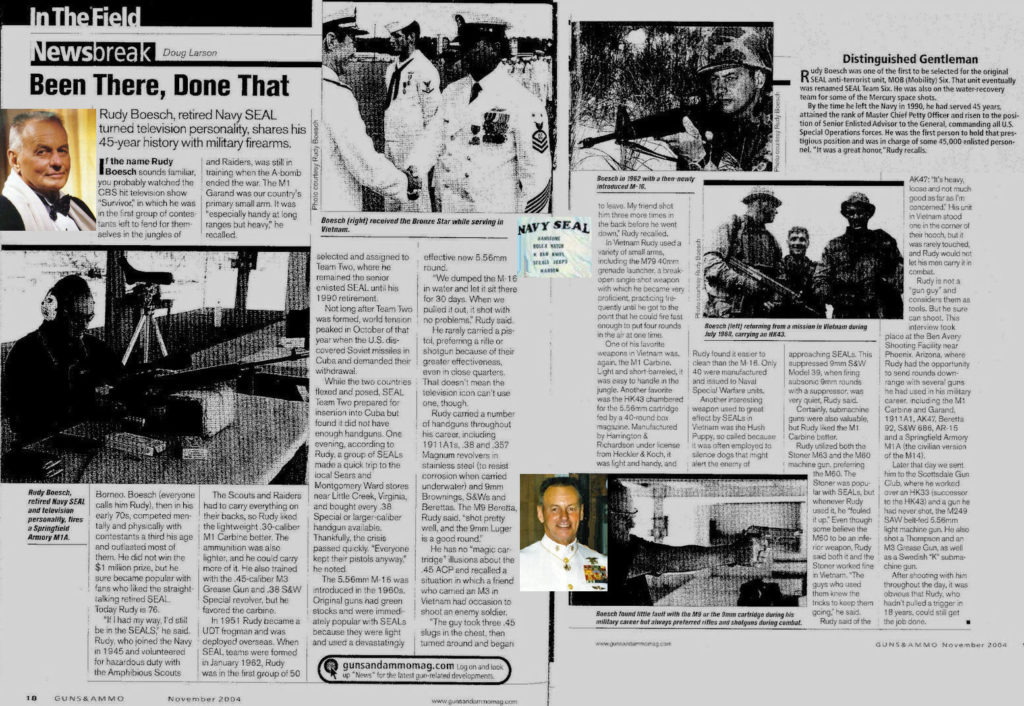

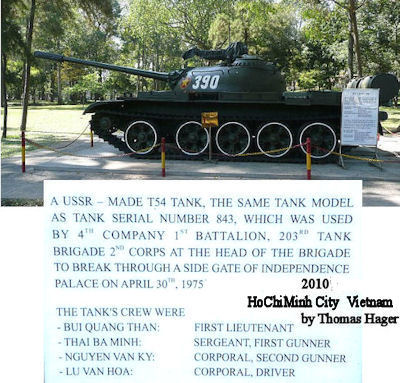

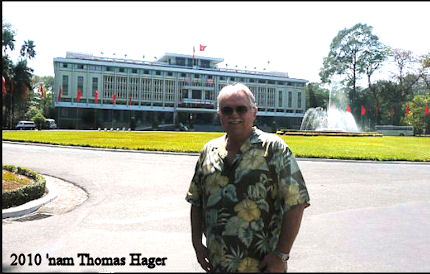

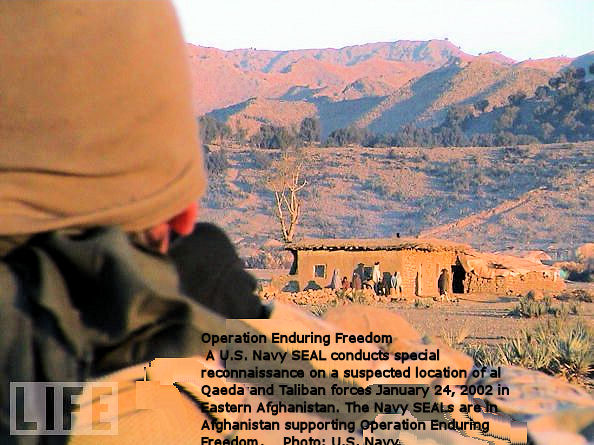

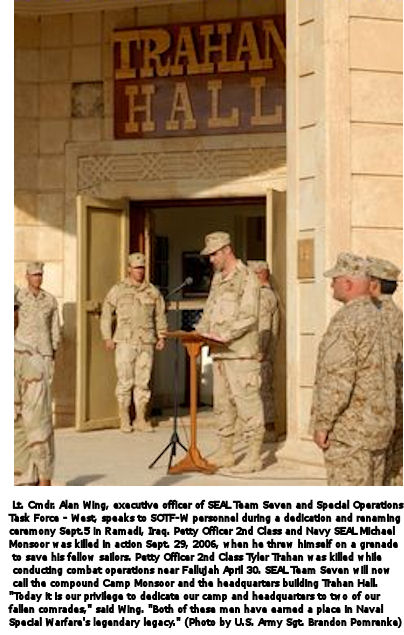

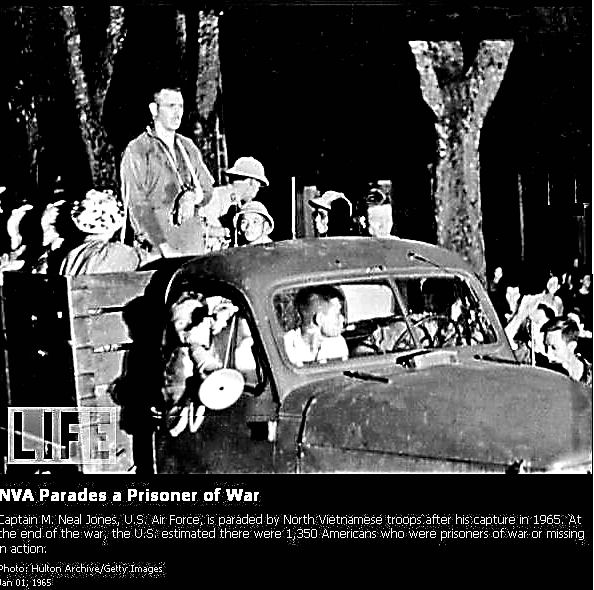

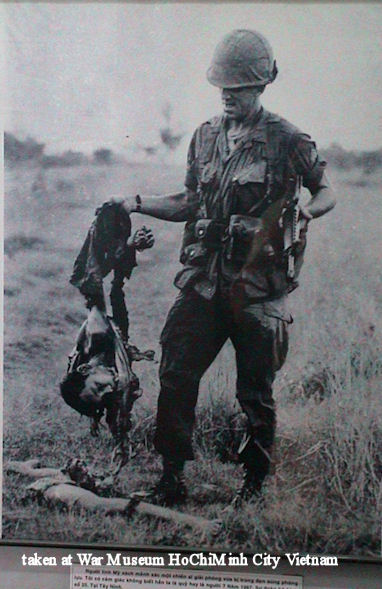

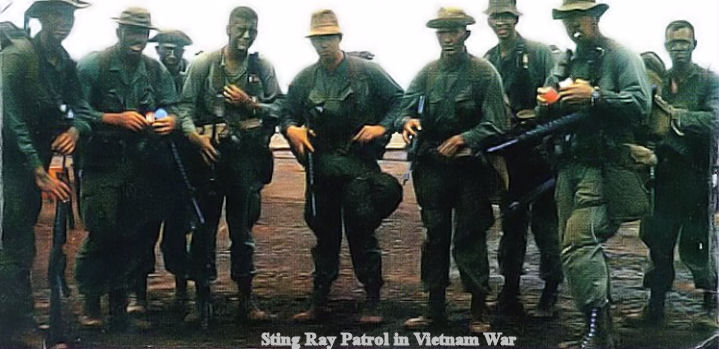

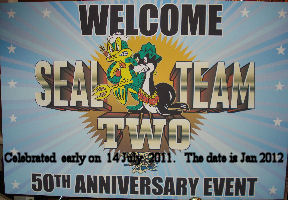

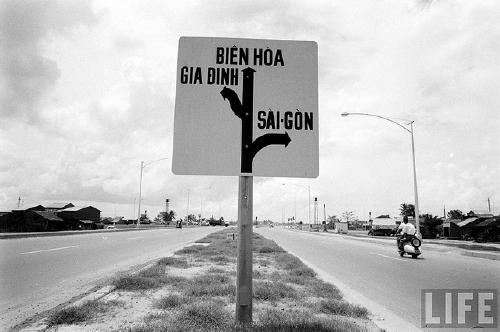

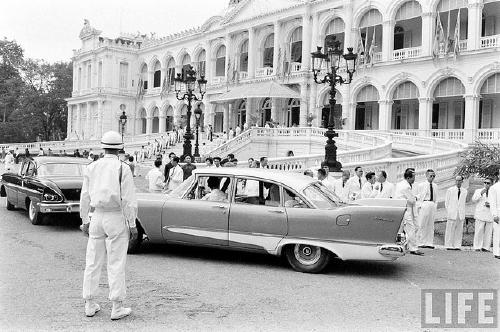

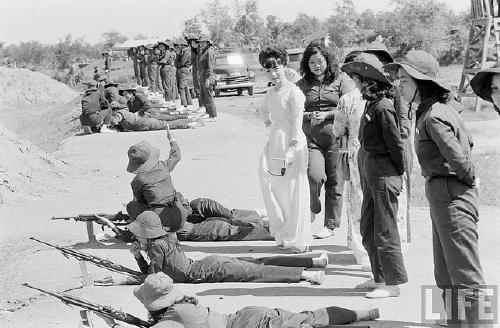

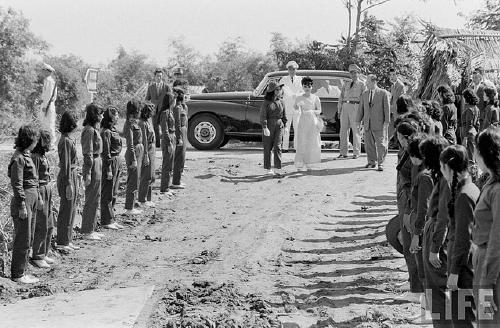

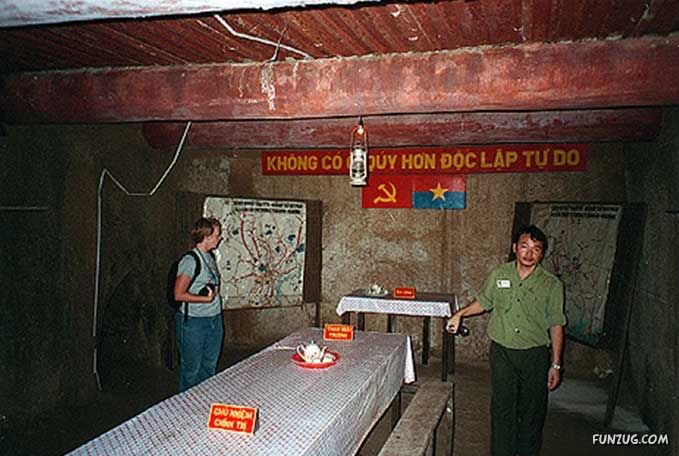

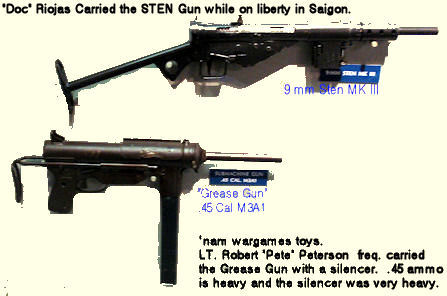

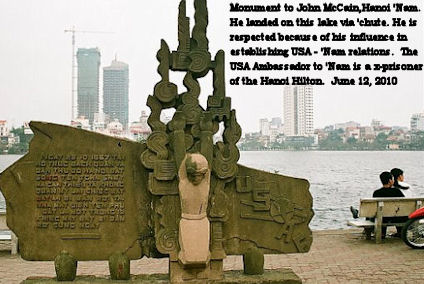

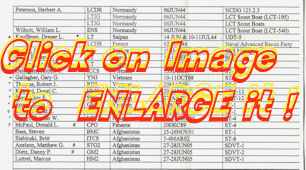

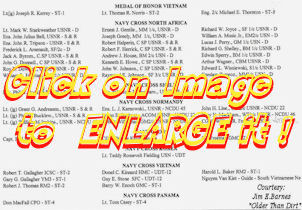

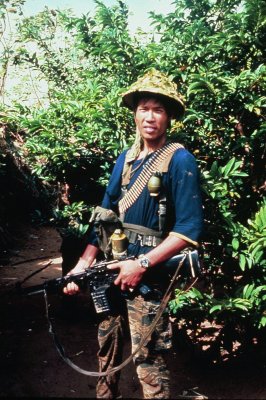

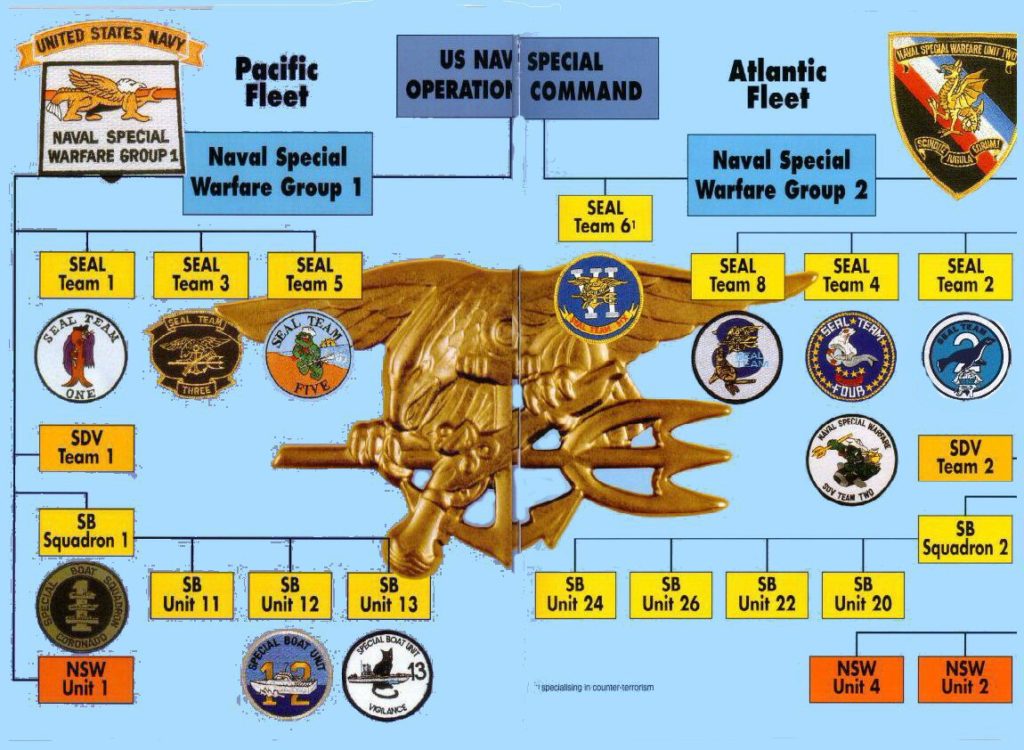

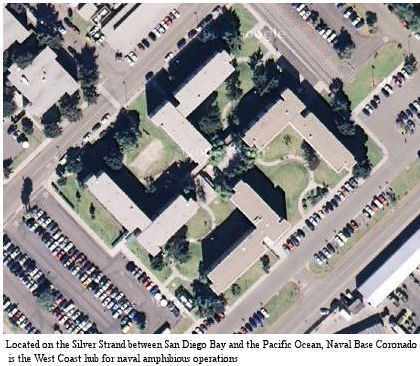

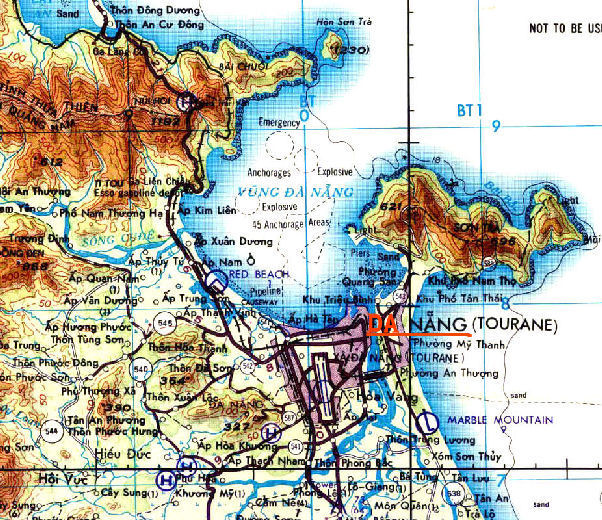

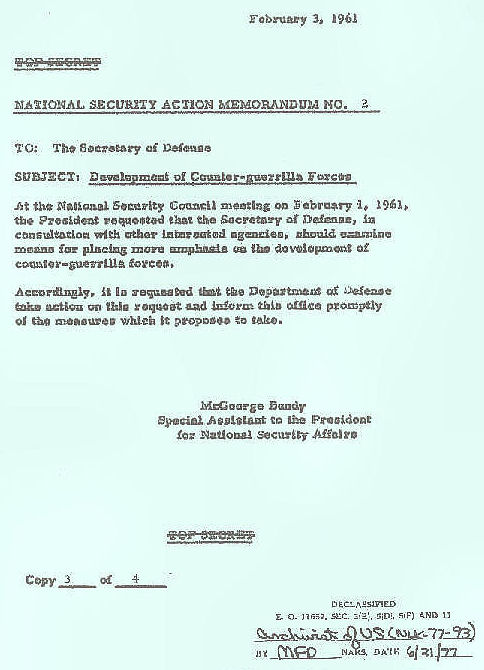

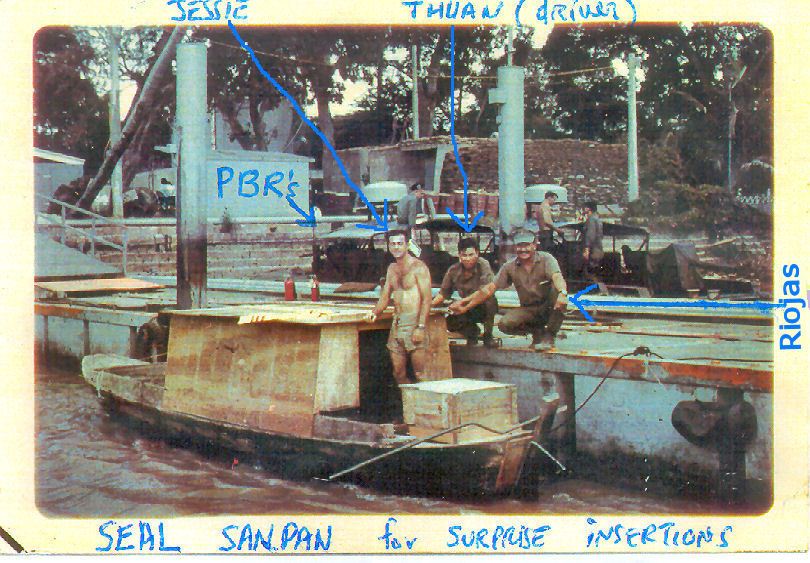

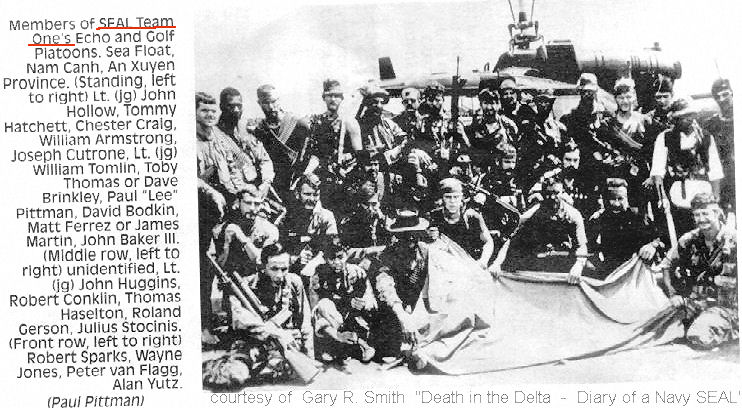

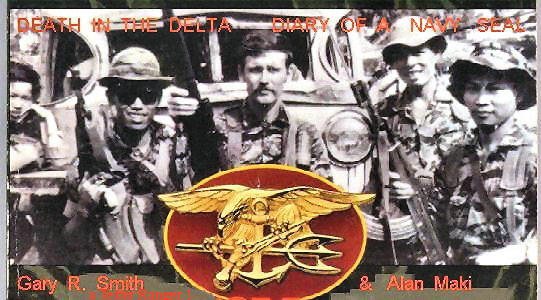

There have been SEAL teams since the Kennedy years, when they got their first real workout against the Vietcong around Da Nang and in the Mekong Delta, and even during periods of relative peace since Vietnam, SEAL teams have been deployed around the world. But at no time have they been more active than in the period since 2001, in the longest war ever fought by Americans. If the surge in Iraq ordered by President Bush in 2007 was at all successful, that success is owed significantly to the night-shift work done by SEAL Team 6.

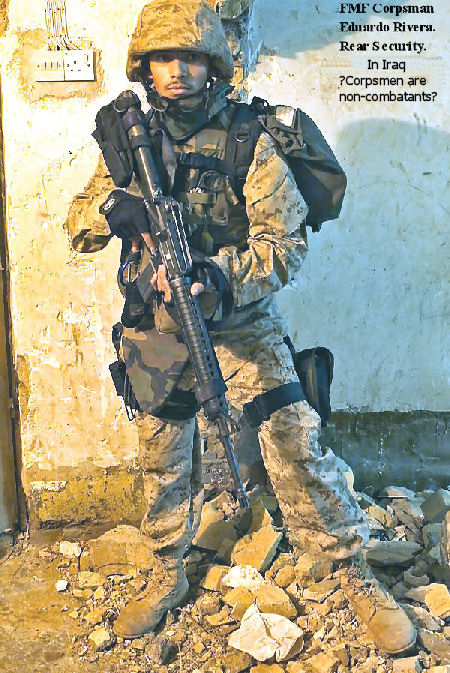

“We would go kill high-value targets every night,” the Shooter tells me. He and other ST6 members who would later be on the Abbottabad trip lived in rough huts with mud floors and cots. “But we were completely disrupting Al Qaeda and other Iraqi networks. If we only killed five or six guys a night, we were wasting our time. We knew this was the greatest moment of our operational lives.”

From Al Asad to Ramadi to Baghdad to Baquba – Al Qaeda central at the time – the SEALs had latitude to go after “everyone we thought we had to kill. That’s really a major reason the surge was going so well, because terrorists were dying strategically.”

During one raid, accompanied by two dogs, the Shooter says that he and his team wiped out “an entire spiderweb network.” Villagers told Iraqi newspapers the next day that “Ninjas came with lions.” It is important to him to stress that no women or children were killed in that raid. He also insists that when it came to interrogation, repetitive questioning and leveraging fear was as aggressive as he’d go. “When we first started the war in Iraq, we were using Metallica music to soften people up before we interrogated them,” the Shooter says. “Metallica got wind of this and they said, ‘Hey, please don’t use our music because we don’t want to promote violence.’ I thought, Dude, you have an album called Kill ‘Em All.

“But we stopped using their music, and then a band called Demon Hunter got in touch and said, ‘We’re all about promoting what you do.’ They sent us CDs and patches. I wore my Demon Hunter patch on every mission. I wore it when I blasted bin Laden.”

On deployment in Afghanistan or Iraq, they would “eat, work out, play Xbox, study languages, do schoolwork.” And watch the biker series Sons of Anarchy, Entourage, and three or four seasons of The Shield.

They were rural high school football stars, backwoods game hunters, and Ivy League graduates thrown together by a serious devotion to the cause, and to the action. Accessories, upbringing, and cultural tastes were just preamble, though, to the real work. As for the Shooter, he jokes that his choice in life was to “go to the SEALs or go to jail.” Not that he would have ever found himself behind bars, but he points out traits that all SEALs seem to have in common: the willingness to live beyond the edge, and to do anything, and the resolve to never quit.

The bin Laden mission was far from the most dangerous of his career. Once, he was pinned down near Asadabad, Afghanistan, while the SEALs were trying to disrupt Al Qaeda supply lines used to ambush Americans.

“Bullets flew between my gun and my face,” he says, just as he was inserting some of his favorite Copenhagen chew and then open-field sprinting to retrieve some special equipment he had dropped. That fight ended when he called in air strikes along the eastern Afghan border to light up the enemy.

Opening a closet door once, team members found a boy inside. “The natural response was ‘C’mon kid.’ Then, boom, he blows himself up. Suicide bombers are fast. Other rooms and other places, “we’d go in and a guy would be sleeping. Up against the wall were his cologne, deodorant, soap, suicide vest, AK-47, and grenades.”

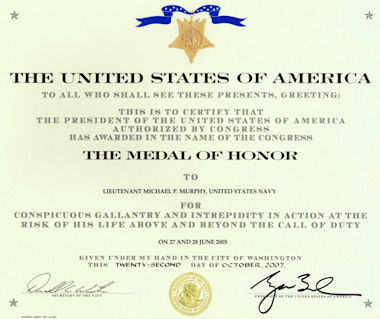

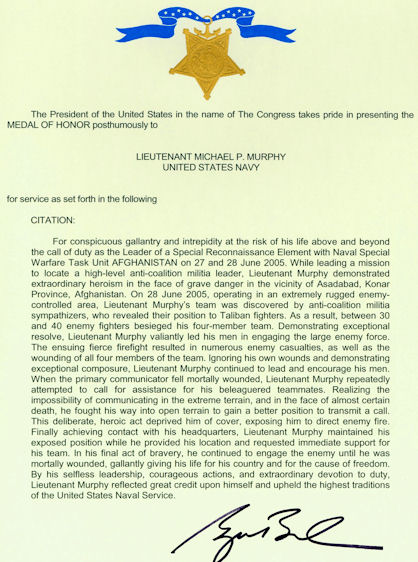

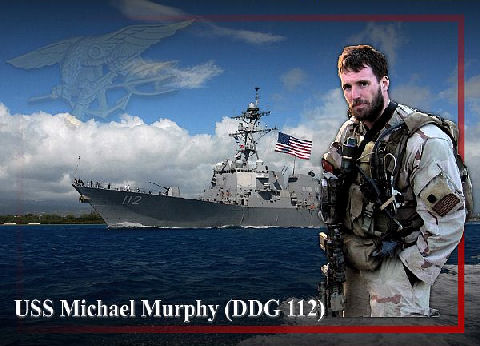

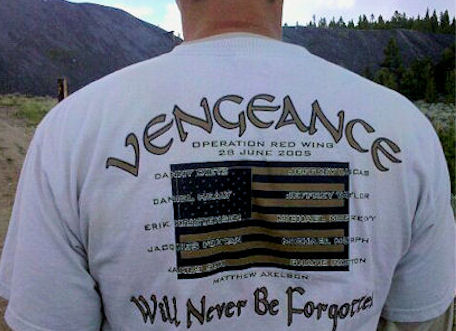

He’s also had to collect body parts of his close friends, most notably when a SEAL team chopper was shot down in Afghanistan’s Kunar province in June 2005, killing eight SEALs. “We go to a lot of funerals.”

But for all the big battle boasts that become a sort of currency among SEALs, the Shooter has a deep fondness for the comedy that comes from being around the bunch of guys who are the only people in the world with whom you have so much in common and the only people in the world who can know exactly what you do for a living.

“I realized when I joined I had to be a better shot and step up my humor. These guys were hilarious.”

There are the now-famous pranks with a giant dildo – they called it the Staff of Power – discovered during training in an abandoned Miami building. SEALs would find photos of it inserted into their gas masks or at the bottom of a barrel of animal crackers they were eating. Goats were put in their personal cages at ST6 headquarters. Uniforms were borrowed and dyed pink. Boots were glued to the floor. Flash-bang grenades went off in their gear.

The area near the Shooter’s cage was such a target for outlandish stunts that it was called the Gaza Strip. Even in action, with all their high state of expertise and readiness, “we’re normal people. We fall off ladders, land on the wrong roof, get bitten by dogs.” In Iraq, a breacher was putting a charge on a door to blow it off its hinges when he mistakenly leaned against the doorbell. He quickly took off the charge and the target opened the door. We were like, “You rang the fucking doorbell?!” Maybe we should try that more often, the Shooter thought to himself.

The dead can also be funny, as long as it’s not your guys. “In Afghanistan we were cutting away the clothes on this dead dude to see if he had a suicide vest on, only to find that he had a huge dick, down to his knees. From then on, we called him Abu Dujan Holmes.

And then there was the time that the Shooter shit himself on a tandem jump with a huge SEAL who outweighed him by sixty pounds. “The goddamn main chute yanked so hard he slipped two disks in his neck and I filled my socks with human feces. I told him, ‘Hey, dude, this is a horrible day.’ He said if I went to our reserve chute, ‘you’re gonna fucking kill me.’ He was that convinced his head was going to rip off his body.

“Okay, so I’m flying this broken chute, shitting my pants with this near-dead guy connected to me. And we eat shit on the landing. We’re lying there and the chute is dragging us across the ground. I hear him go, ‘Yeah, that’s my last jump for today.’ And I said, ‘That’s cool. Can I borrow your boxers?’

“We jumped the next day.” The Shooter’s willingness to endure comes from a deep personal well of confidence and drive that seems to also describe every one of his peers. But his odyssey through countless outposts in Afghanistan and Iraq to skydives into the Indian Ocean – situations that are always strewn with violence and with his own death always imminent – is grounded by a sense of deep confederacy. “I’m lucky to be with these guys. I’m not going to let them down. I was going to go in for a few years, but then I met these other guys and stuck around because of them.” He and one buddy made their first kills at exactly the same time, in Ramadi. Shared bloodletting is as much a bonding agent as shared blood.

After Team 6 SEAL Adam Brown was killed in March 2010, Brown’s squadron members approached the dead man’s kids at the funeral. They were screaming and inconsolable. “You may have lost a father,” one of them said, “but you’ve gained twenty fathers.”

Most of those SEALs would be killed the next year when their helicopter was shot down in eastern Wardak province.

The Shooter feels both the losses and connections no less keenly now that he’s out. “One of my closest friends in the world I’ve been with in SEAL Team 6 the whole time,” he says. The Shooter’s friend is also looking for a viable exit from the Navy. As he prepared to deploy again, he agreed to talk with me on the condition that I not identify him.

“My wife doesn’t want me to stay in one more minute than I have to,” he says. But he’s several years away from official retirement. “I agree that civilian life is scary. And I’ve got a family to take care of. Most of us have nothing to offer the public. We can track down and kill the enemy really well, but that’s it.

“If I get killed on this next deployment, I know my family will be taken care of.” (The Navy does offer decent life-insurance policies at low rates.) “College will be paid for, they’ll be fine.

“But if I come back alive and retire, I won’t have a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out for the rest of my life. Sad to say, it’s better if I get killed.”

4.”IS THIS THE BEST THING I’VE EVER DONE, OR THE WORST?“

When we entered the main building, there was a hallway with rooms off to the side. Dead ahead is the door to go upstairs. There were women screaming downstairs. They saw the others get shot, so they were upset. I saw a girl, about five, crying in the corner, first room on the right as we were going in. I went, picked her up, and brought her to another woman in the room on the left so she didn’t have to be just with us. She seemed too out of it to be scared. There had to be fifteen people downstairs, all sleeping together in that one room. Two dead bodies were also in there.

Normally, the SEALs have a support or communications guy who watches the women and children. But this was a pared-down mission intended strictly for an assault, without that extra help. We didn’t really have anyone that could stay back. So we’re looking down the hallway at the door to the stairwell. I figured this was the only door to get upstairs, which means the people upstairs can’t get down. If there had been another way up, we would have found it by then.

We were at a standstill on the ground floor, waiting for the breacher to do his work. We’d always assumed we’d be surrounded at some point. You see the videos of him walking around and he’s got all those jihadis. But they weren’t prepared. They got all complacent. The guys that could shoot shot, but we were on top of them so fast.

Right then, I heard one of the guys talking about something, blah, blah, blah, the helo crashed. I asked, What helo crashed? He said it was in the yard. And I said, Bullshit! We’re never getting out of here now. We have to kill this guy. I thought we’d have to steal cars and drive to Islamabad. Because the other option was to stick around and wait for the Pakistani military to show up. Hopefully, we don’t shoot it out with them. We’re going to end up in prison here, with someone negotiating for us, and that’s just bad. That’s when I got concerned.

I’ve thought about death before, when I’ve been pinned down for an hour getting shot at. And I wondered what it was going to feel like taking one of those in the face. How long was it going to hurt? But I didn’t think about that here.

One of the snipers who’d seen the disabled helo approached just before they went into the main building. He said, “Hey, dude, they’ve got an awesome mock-up of our helo in their yard.” I said, “No, dude. They shot one of ours down.” He said, “Okay, that makes more sense than the shit I was saying.”

The breacher had to blast the door twice for it to open. We started rolling up. Team members didn’t need much communication, or any orders, once they were on line. We’re reading each other every second. We’ve gotten so good at war, we didn’t need anything more.

I was about five guys back on the stairway when I saw the point man holding up. He’d seen Khalid, bin Laden’s [twenty-three-year-old] son. I heard him whisper, “Khalid… come here…” in Arabic, then in Pashto. He used his name. That confused Khalid. He’s probably thinking, “I just heard shitty Arabic and shitty Pashto. Who the fuck is this?” He leaned out, armed with an AK, and he got blasted by the point man. That call-out was one of the best combat moves I’ve ever seen. Khalid had on a white T-shirt and, like, white pajama pants. He was the last line of security.

I remember thinking then: I wish we could live through this night, because this is amazing. I was still expecting all kinds of funky shit like escape slides or safe rooms.

The point man moved past doors on the second floor and the four or five guys in front of me started to peel off to clear those rooms, which is always how the flow works. We’re just clearing as we go, watching our backs.

They step over and past Khalid, who’s dead on the stairs. The point man, at that time, saw a guy on the third floor, peeking around a curtain in front of the hallway. Bin Laden was the only adult male left to find. The point man took a shot, maybe two, and the man upstairs disappeared back into a room. I didn’t see that because I was looking back. I don’t think he hit him. He thinks he might have. So there’s the point man on the stairs, waiting for someone to move into the number-two position. Originally I was five or six man, but the train flowed off to clear the second floor. So I roll up behind him. He told me later, “I knew I had some ass,” meaning somebody to back him up. I turn around and look. There’s nobody else coming up.

On the third floor, there were two chicks yelling at us and the point man was yelling at them and he said to me, “Hey, we need to get moving. These bitches is getting truculent.” I remember saying to myself, Truculent? Really? Love that word.

I kept looking behind us, and there was still no one else there.

By then we realized we weren’t getting more guys. We had to move, because bin Laden is now going to be grabbing some weapon because he’s getting shot at. I had my hand on the point man’s shoulder and squeezed, a signal to go. The two of us went up. On the third floor, he tackled the two women in the hallway right outside the first door on the right, moving them past it just enough. He thought he was going to absorb the blast of suicide vests; he was going to kill himself so I could get the shot. It was the most heroic thing I’ve ever seen.

I rolled past him into the room, just inside the doorway. There was bin Laden standing there. He had his hands on a woman’s shoulders, pushing her ahead, not exactly toward me but by me, in the direction of the hallway commotion. It was his youngest wife, Amal.

The SEALs had nightscopes, but it was coal-black for bin Laden and the other residents. He can hear but he can’t see.

He looked confused. And way taller than I was expecting. He had a cap on and didn’t appear to be hit. I can’t tell you 100 percent, but he was standing and moving. He was holding her in front of him. Maybe as a shield, I don’t know.

For me, it was a snapshot of a target ID, definitely him. Even in our kill houses where we train, there are targets with his face on them. This was repetition and muscle memory. That’s him, boom, done.

I thought in that first instant how skinny he was, how tall and how short his beard was, all at once. He was wearing one of those white hats, but he had, like, an almost shaved head. Like a crew cut. I remember all that registering. I was amazed how tall he was, taller than all of us, and it didn’t seem like he would be, because all those guys were always smaller than you think.

I’m just looking at him from right here [he moves his hand out from his face about ten inches]. He’s got a gun on a shelf right there, the short AK he’s famous for. And he’s moving forward. I don’t know if she’s got a vest and she’s being pushed to martyr them both. He’s got a gun within reach. He’s a threat. I need to get a head shot so he won’t have a chance to clack himself off [blow himself up].

In that second, I shot him, two times in the forehead. Bap! Bap! The second time as he’s going down. He crumpled onto the floor in front of his bed and I hit him again, Bap! same place. That time I used my EOTech red-dot holo sight. He was dead. Not moving. His tongue was out. I watched him take his last breaths, just a reflex breath.

And I remember as I watched him breathe out the last part of air, I thought: Is this the best thing I’ve ever done, or the worst thing I’ve ever done? This is real and that’s him. Holy shit.

Everybody wanted him dead, but nobody wanted to say, Hey, you’re going to kill this guy. It was just sort of understood that’s what we wanted to do.

His forehead was gruesome. It was split open in the shape of a V. I could see his brains spilling out over his face. The American public doesn’t want to know what that looks like.

Amal turned back, and she was screaming, first at bin Laden and then at me. She came at me like she wanted to fight me, or that she wanted to die instead of him. So I put her on the bed, bound with zip ties. Then I realized that bin Laden’s youngest son, who is about two or three, was standing there on the other side of the bed. I didn’t want to hurt him, because I’m not a savage. There was a lot of screaming, he was crying, just in shock. I didn’t like that he was scared. He’s a kid, and had nothing to do with this. I picked him up and put him next to his mother. I put some water on his face.

The point man came in and zip-tied the other two women he’d grabbed.

The third-floor action and killing took maybe fifteen seconds.

The Shooter’s oldest child calls the place his dad worked “Crapghanistan,” maybe because his deployments meant he regularly missed Christmases, birthdays, and other holidays.

“Our marriage was definitely a casualty of his career,” says the Shooter’s wife. They are officially split but still live together. Separate bedrooms, low overhead. “Somewhere along the line we lost track of each other.” She holds his priorities partially responsible: SEAL first, father second, husband third.

This part of the Shooter’s story is, as his wife puts it, “unique to us but unfortunately not unique in the community.”

SEAL operators are gone up to three hundred days a year. And when they’re not in theater, they’re training or soaking in the company of their buds in the absorbing clubhouse atmosphere of ST6 headquarters.

“We can’t talk with anyone else about what we do,” the Shooter says, “or about anything else other than maybe skydiving and broken spleens. When it comes to socializing, it’s really tight.”

His wife understands that “so much of their survival is dependent on the fact that their friends and their jobs are so intertwined.” And that “we lived our lives under a veil of secrecy.”

SEAL Team 6 spouses are nicknamed the Pink Squadron, because the women also rely on their hermetic connections to other wives. When you have no idea where your husband is or what he’s doing, other than that it’s mortally dangerous, and you can’t discuss it – not even with your own mother – your world can feel desperately small.

But his wife’s concerns, and her own narrative, convey a faithfulness that extends beyond marital fidelity.

She has comforted him when he was “inconsolable” after a mission in which he shot the parents of a boy in a crossfire. “He was reliving it, as a dad himself, when he was telling me.” Not long after, she tended to him when she found him heavily sedated with an open bottle of Ambien and his pistol nearby.

The command had mandatory psych evaluations. During one of those, the Shooter told the psychologist, “I was having suicidal thoughts and drinking too much.” The doctor’s response? “He told me this was normal for SEALs after combat deployment. He told me I should just drink less and not hurt anybody.”

The Shooter’s wife is indignant. “That’s not normal!” Though she knows that “every time you send your husband off to war, you get a slightly different person back.”

The alone times are deeply trying.

Several years ago, a SEAL friend had died in a helicopter crash. The Shooter’s wife had just been to his funeral, consoling his widow. The Shooter was on the same deployment, and she had not heard anything about his status.

“I came home and was inside holding our infant child. Our front door is all glass, and I see a man in a khaki uniform coming up the steps. All I could do was think, I’d better put the baby down because I’m going to faint. So I set the baby on the floor and answered the door. It was a neighbor with a baby bib I’d dropped outside. I swore at him and slammed the door in his face.”

It was four days more before she heard that her husband was safe.

Given all of that, she has a surprising equanimity about her life. Talking with them separately, the couple’s love for each other is evident and deep. “We’ve grown so much together,” she says. “We’ll always be best friends. I’ll love him till the day I die.”

She remains in awe of “the level of brilliance these men have. To be surrounded by that caliber of people is something I’ll always be grateful for.” Her husband’s retirement has been no less jarring for her. “He gave so much to his country, and now it seems he’s left in the dust. I feel there’s no support, not just for my family but for other families in the community. I honestly have nobody I can go to or talk to. Nor do I feel my husband has gotten much for what he’s accomplished in his career.”

Exactly what, if any, responsibility should the government have to her family?

The loss of income and insurance and no pension aside, she can no longer walk onto the local base if she feels a threat to her family. They’ve surrendered their military IDs. If something were to happen, the Shooter has instructed her to take the kids to the base gate anyway and demand to see the commanding officer, or someone from the SEAL team. “He said someone will come get us.” Because of the mission, she says that “my family is always going to be at risk. It’s just a matter of finding coping strategies.”

The Shooter still dips his hand in his pocket when they’re in a store, checking for a knife in case there’s an emergency. He also keeps his eyes on the exits. He’s lost some vision, he can’t get his neck straight for any period of time. Right now, she’s just waiting to see what he creates for himself in this new life.

And she’s waiting to see how he replaces even the $60,000 a year he was making (with special pay bonuses for different activities). Or how they can afford private health insurance that covers spinal injections she needs for her own sports injuries.

“This is new to us, not having the team.”

5.”WE ALL DID IT.” Within another fifteen seconds, other team members started coming in the room. Here, the Shooter demurs about whether subsequent SEALs also fired into bin Laden’s body. He’s not feeding raw meat to what is an increasingly strict government focus on the etiquette of these missions. But I would have done it if I’d come in the room later. I knew I was going to shoot him if I saw him, regardless.

I even joked about that with the guys before we were there. “I don’t give a shit if you kill him – if I come in the room, I’m shooting his ass. I don’t care if he’s deader than fried chicken.”

In the compound, I thought about getting my camera, and I knew we needed to take pictures and ID him. We had a saying, “You kill him, you clean him.” But I was just in a little bit of a zone. I had to actually ask one of my friends who came into the room, “Hey, what do we do now?” He said, “Now we go find the computers.” And I remember saying, “Yes! I’m back! Got it!” Because I was almost stunned.

Then I just wanted to go get out of the house. We all had a DNA test kit, but I knew another team would be in there to do all that. So I went down to the second floor where the offices were, the media center. We started breaking apart the computer hard drives, cracking the towers. We were looking for thumb drives and disks, throwing them into our net bags.

In each computer room, there was a bed. Under the beds were these huge duffel bags, and I’m pulling them out, looking for whatever. At first I thought they were filled with vacuum-sealed rib-eye steaks. I thought, They’re in this for the long haul. They’ve got all this food. Then, wait a minute. This is raw opium. These drugs are everywhere. It was pretty funny to see that.

Altogether, he helped clean three rooms on the second floor. The Shooter did not see bin Laden’s body again until he and the point man helped two others carry it, already bagged, down the building’s hallways and out into the courtyard by the front gate. I saw a sniper buddy of mine down there and I told him, “That’s our guy. Hold on to him.” Others took the corpse to the surviving Black Hawk.

With one helo down, the Shooter was relieved to hear the sound of the 47 Chinook transports arriving. His exfil (extraction) flight out was on one of the 47’s, which had almost been blown out of the sky by the SEALs’ own explosive charges, set to destroy the downed Black Hawk.

One backup SEAL Team 6 member on the flight asked who’d killed UBL. I said I fucking killed him. He’s from New York and says, “No shit. On behalf of my family, thank you.” And I thought: Wow, I’ve got a Navy SEAL telling me thanks?

“You probably thought you’d never hear this,” someone piped through the intercom system over an hour into the return flight, “but welcome back to Afghanistan.”

Back at the Jalalabad base, we pulled bin Laden out of the bag to show McRaven and the CIA. That’s when McRaven had a tall SEAL lie down next to bin Laden to assess his height, along with other, slightly more scientific identity tests.

With the body laid out and under inspection, you could see more gunshot wounds to bin Laden’s chest and legs.

While they were still checking the body, I brought the agency woman over. I still had all my stuff on. We looked down and I asked, “Is that your guy?” She was crying. That’s when I took my magazine out of my gun and gave it to her as a souvenir. Twenty-seven bullets left in it. “I hope you have room in your backpack for this.” That was the last time I saw her.

From there, the team accompanied the body to nearby Bagram Airfield. During the next few hours, the thought that hit me was “This is awesome. This is great. We lived. This is perfect. We just did it all.”

The moment truly struck at Bagram when I’m eating a breakfast sandwich, standing near bin Laden’s body, looking at a big-screen TV with the president announcing the raid. I’m sitting there watching him, looking at the body, looking at the president, eating a sausage-egg-cheese-and-extra-bacon sandwich thinking, “How the fuck did I get here? This is too much.”

I still didn’t know if it would be good or bad. The good was having done something great for my country, for the guys, for the people of New York. It was closure. An honor to be there. I never expected people to be screaming “U.S.A.!” with Geraldo outside the White House.

The bad part was security. He was their prophet, basically. Now we killed him and I have to worry about this forever. Al Qaeda, especially these days, is 99 percent talk. But that 1 percent of the time they do shit, it’s bad. They’re capable of horrific things.

We listened to the Al Qaeda phone calls where one guy is saying, “We gotta find out who ratted on bin Laden.” The other guy says, “I heard he did it to himself. He was locked up in that house with three wives.” Funny terrorists.

At Bagram, the point man asked, “Hey, was he hit when you went into the room? I thought I shot him in the head and his cap flew off.” I said I didn’t know, but he was still walking and he had his hat on. The point man was like “Okay. No big deal.” By then we had showered and were having some refreshments. We weren’t comparing dicks. I’ve been in a lot of battles with this guy. He’s a fucking amazing warrior, the most honorable, truthful dude I know. I trust him with my life.

The Shooter said he and the point man participated in a shooters-only debrief with military officials around a trash can in Jalalabad and then a long session at Bagram Airfield, but they left some details ambiguous. The point man said he took two shots and thought one may have hit bin Laden. He said his number two went into the room “and finished him off as he was circling the drain.” This was not exactly as it had gone down, but everyone seemed satisfied.

Early government versions of the shooting talked about bin Laden using his wife as protection and being shot by a SEAL inside the room. But subsequent accounts, from officials and others like Bissonnette, further muddied the story and obscured the facts.

What the two SEALs did discuss after the action was why there’d been a short gap before more assaulters joined them on the third floor. “Where was everybody else?” the point man asked. I told him we just ran thin.

Guys went left and right on the second floor and it was just us. Everything happened really fast. Everybody did their jobs. Any team member would have done exactly what I did.

At Jalalabad, as we got off the plane there was an air crew there, guys who fix helicopters. They hugged me and knew I’d killed him. I don’t know how the hell word spread that fast.

McRaven himself came over to me, very emotional. He grabbed me across the back of my neck like a proud father and gave me a hug. He knew what had happened, too.

Not long after, a senior government official had an unofficial phone call with the mentor. “Your boy was the one,” the mentor says he was told. The Shooter was alternately shocked and pleased to know that word got back to the States before I did. “Who killed bin Laden?” was the first question, and then the name just flies.

And it was the Shooter who, when an Obama administration official asked for details during the president’s private visit with the bin Laden team at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, said “We all did it.”

The SEAL standing next to the Shooter would say later, “Man, I was dying to tell him it was you.”

From the moment reporters started getting urgent texts hours before President Obama’s official announcement on May 1, 2011, the bin Laden mission exploded into public view. Suddenly, a brilliant spotlight was shining where shadows had ruled for decades.

TV trucks descended on the SEAL Team 6 community in Virginia Beach, showing their homes and hangouts.

“The big mission changed a lot of attitudes around the command,” the Shooter says. “There were suspicions about whether anyone was selling out.”

It had begun “when we were still in the Jalalabad hangar with our shit on. There was a lot of ‘Don’t let this go to your head, don’t talk to anyone,’ not even our own Red Team guys who hadn’t gone with us.”

The assaulters “were immediately put in a box, like a time-out,” says the Shooter’s close friend, who was not on the mission. “‘Don’t open your mouth.’ I would have flown them to Tahoe for a week.”

But even with the SEALs’ strong history of institutional modesty, there was no unringing this bell.

The potential for public fame was too great, and suspicion was high inside SEAL Team 6.

The Shooter was among those reprimanded for going out to a bar to celebrate the night they got back home. And he was supposed to report for work the next morning, but instead took the day off to spend with his kids.

Twenty-four hours later came the offer of witness protection, driving the beer truck in Milwaukee. “That was the best idea on the table for security.”

“Maybe some courtesy eyes-on checks” of his home, he thought. “Send some Seabees over to put in a heavier, metal-reinforced front door. Install some sensors or something. But there was literally nothing.” He considered whether to get a gun permit for life outside the perimeter. The SEALs are proud of being ready for “anything and everything.” But when it came to his family’s safety? “I don’t have the resources.”

With gossip and finger-pointing continuing over the mission, the Shooter made a decision “to show I wasn’t a douchebag, that I’m still part of this team and believe in what we’re doing.”

He re-upped for another four-month deployment. It would be in the brutal cold of Afghanistan’s winter.

But he had already decided this would be his last deployment, his SEAL Team 6 sayonara.

“I wanted to see my children graduate and get married.” He hoped to be able to sleep through the night for the first time in years. “I was burned out,” he says. “And I realized that when I stopped getting an adrenaline rush from gunfights, it was time to go.”

May 1, 2012, the first anniversary of the bin Laden mission. The Shooter is getting ready to go play with his kids at a water park. He’s watching CNN.

“They were saying, ‘So now we’re taking viewer e-mails. Do you remember where you were when you found out Osama bin Laden was dead?’ And I was thinking: Of course I remember. I was in his bedroom looking down at his body.”

The standing ovation of a country in love with its secret warriors had devolved into a news quiz, even as new generations of SEALs are preparing for sacrifice in the Horn of Africa, Iran, perhaps Mexico.

The Shooter himself, an essential part of the team helping keep us safe since 9/11, is now on his own. He is enjoying his family, finally, and won’t be kissing his kids goodbye as though it were the last time and suiting up for the battlefield ever again.

But when he officially separates from the Navy three months later, where do his sixteen years of training and preparedness go on his résumé? Who in the outside world understands the executive skills and keen psychological fortitude he and his First Tier colleagues have absorbed into their DNA? Who is even allowed to know? And where can he go to get any of these questions answered?

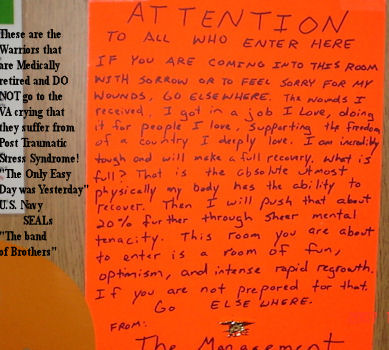

There is a Transition Assistance Program in the military, but it’s largely remedial level, rote advice of marginal value: Wear a tie to interviews, not your Corfam (black shiny service) shoes. Try not to sneeze in anyone’s coffee. There is also a program at MacDill Air Force Base designed to help Special Ops vets navigate various bureaucracies. And the VA does offer five years of health care benefits-through VA physicians and hospitals-for veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan but it offers nothing for the shooter’s family.

“It’s criminal to me that these guys walk out the door naked,” says retired Marine major general Mike Myatt. “They’re the greatest of their generation; they know how to get things done. If I were a Fortune 500 company, I’d try to get my hands on any one of them.” The general is standing in the mezzanine of the Marines Memorial building he runs in San Francisco. He’s had to expand the memorial around the corner due to so many deaths over the past eleven years of war.

He is furious about the high unemployment rate among returning infantrymen, as well as homelessness, PTSD, and the other plagues of new veterans. General Myatt believes “the U.S. military is the best in the world at transitioning from civilian to military life and the worst in the world at transitioning back.” And that, he acknowledges, doesn’t even begin to consider the separate and distinct travesty visited on the Shooter and his comrades.

The Special Operations men are special beyond their operations. “These guys are self-actualizers,” says a retired rear admiral and former SEAL I spoke with. “Top of the pyramid. If they wanted to build companies, they could. They can do anything they put their minds to. That’s how smart they are.”

But what’s available to these superskilled retiring public servants? “Pretty much nothing,” says the admiral. “It’s ‘Thank you for your service, good luck.'”

One third-generation military man who has worked both inside and outside government, and who has fought for vets for decades, is sympathetic to the problem. But he notes that the Pentagon is dealing with two hundred thousand new veterans a year, compared with perhaps a few dozen SEALs. “Can and should the DOD spend the extra effort it would take to help the superelite guys get with exactly the kind of employers they should have? Investment bankers, say, value that competition, drive, and discipline, not to mention people with security clearances. They [Tier One vets] should be plugged in at executive levels. Any employers who think about it would want to hire these people.”

For officials, however, everyone signing out of war is a hero, and even for the masses of retirees, programs are sporadic and often ineffectual. Michelle Obama and Jill Biden have both made transitioning vets a personal cause, though these efforts are largely gestural and don’t reach nearly high enough for the skill sets of a member of SEAL Team 6.

The Virginia-based Navy SEAL Foundation has a variety of supportive programs for the families of SEALs, and the foundation spends $3.2 million a year maintaining them. But as yet they have no real method or programs for upper-level job placement of their most practiced constituency.

A businessman associated with the foundation says he understands that there is a need the foundation does not fill. “This is an ongoing thing where lots of people seem to want to help but no one has ever really done it effectively because our community is so small. No one’s ever cracked it. And there real-ly needs to be an education effort well before they separate [from the service] to tell them, ‘The world you’re about to enter is very different than the one you’ve been operating in the last fifteen or twenty years.'”

One former SEAL I spoke with is a Harvard MBA and now a very successful Wall Street trader whose career path is precisely the kind of example that should be evangelized to outgoing SEALs. His own life reflects that “SpecOps guys could be hugely value-added” to civilian companies, though he says business schools – degrees in general – might be an important step. “It would be great to get a panel of CEOs together who are ready to help these guys get hired.” Some big companies do have veteran-outreach specialists – former SEAL Harry Wingo fills that role at Google.

But these individual and scattered shots still do not provide what is needed: a comprehensive battle plan.

In San Francisco recently, I talked about the Special Ops issue with Twitter CEO Dick Costolo and venture capitalist and Orbitz chairman Jeff Clarke. Both are very interested in offering a business luminary hand to help clandestine operators make their final jump. There is enthusiastic consensus among the business and military people I have canvassed that this kind of outside help is required, perhaps a new nonprofit financed and driven by the Costolos and Clarkes of the world.

Even before he retired, the Shooter’s new business plan dissolved when the SEAL Team 6 members who formed it decided to go in different directions, each casting for a civilian professional life that’s challenging and rewarding. The stark realities of post-SEAL life can make even the blood of brothers turn a little cold.

“I still have the same bills I had in the Navy,” the Shooter tells me when we talk in September 2012. But no money at all coming in, from anywhere.

“I just want to be able to pay all those bills, take care of my kids, and work from there,” he says. “I’d like to take the things I learned and help other people in any way I can.” In the last few months, the Shooter has put together some work that involves a kind of discreet consulting for select audiences. But it’s a per-event deal, and he’s not sure how secure or long-term it will be. And he wants to be much more involved in making the post – SEAL Team 6 transition for others less uncertain.

The December suicide of one SEAL commander in Afghanistan and the combat death of another – a friend – while rescuing an American doctor from the Taliban underscore his urgent desire to make a difference on behalf of his friends.

He imagines traveling back to other parts of the world for a few days at a time to do dynamic surveys for businesses looking to put offices in countries that are not entirely safe, or to protect employees they already have in place.

But he is emphatic: He does not want to carry a gun. “I’ve fought all the fights. I don’t have a need for excitement anymore. Honestly.”

After all, when you’ve killed the world’s most wanted man, not everything should have to be a battle.

“They torture the shit out of people in this movie, don’t they? Everyone is chained to something.”

The Shooter is sitting next to me at a local movie theater in January, watching Zero Dark Thirty for the first time. He laughs at the beginning of the film about the bin Laden hunt when the screen reads, “Based on firsthand accounts of actual events.”

His uncle, who is also with us, along with the mentor and the Shooter’s wife, had asked him earlier whether he’d seen the film already.

“I saw the original,” the Shooter said. As the action moves toward the mission itself, I ask the Shooter whether his heart is beating faster. “No,” he says matter-of-factly. But when a SEAL Team 6 movie character yells, “Breacher!” for someone to blow one of the doors of the Abbottabad compound, the Shooter says loudly, “Are you fucking kidding me? Shut up!”

He explains afterward that no one would ever yell, “Breacher!” during an assault. Deadly silence is standard practice, a fist to the helmet sufficient signal for a SEAL with explosive packets to go to work.

During the shooting sequence, which passes, like the real one, in a flash, his fingers form a steeple under his chin and his focus is intense.

But his criticisms at dinner afterward are minor.

“The tattoo scene was horrible,” he says about a moment in the film when the ST6 assault group is lounging in Afghanistan waiting to go. “Those guys had little skulls or something instead of having some real ink that goes up to here.” He points to his shoulder blade.

“It was fun to watch. There was just little stuff. The helos turned the wrong way [toward the target], and they talked way, way too much [during the assault itself]. If someone was waiting for you, they could track your movements that way.”

The tactics on the screen “sucked,” he says, and “the mission in the damn movie took way too long” compared with the actual event. The stairs inside bin Laden’s building were configured inaccurately. A dog in the film was a German shepherd; the real one was a Belgian Malinois who’d previously been shot in the chest and survived. And there’s no talking on the choppers in real life.

There was also no whispered calling out of bin Laden as the SEALs stared up the third-floor stairwell toward his bedroom. “When Osama went down, it was chaos, people screaming. No one called his name.”

“They Hollywooded it up some.”

The portrayal of the chief CIA human bloodhound, “Maya,” based on a real woman whose iron-willed assurance about the compound and its residents moved a government to action, was “awesome” says the Shooter. “They made her a tough woman, which she is.”

The Shooter and the mentor joke with each other about the latest thermal/night-vision eyewear used in the movie, which didn’t exist when the older man was a SEAL.

“Dude, what the fuck? How come I never got my four-eye goggles?” “We have those.” “Are you kidding me?”

“SEAL Team 6, baby.”

They laugh, at themselves as much as at each other.

The Shooter seems smoothed out, untroubled, as relaxed as I’ve seen him. But the conversation turns dark when they discuss the portrayal of the other CIA operative, Jennifer Matthews, who was among seven people killed in 2009 when a suicide bomber was allowed into one of their black-ops stations in Afghanistan.

They both knew at least one of the paramilitary contractors who perished with her. The supper table is suddenly flooded with the surge of strong emotions. Anguish, really, though they both hide it well. This is not a movie. It’s real life, where death is final and threats last forever.

The blood is your own, not fake splatter and explosive squibs.

Movies, books, lore – we all helped make these men brilliant assassins in the name of liberty, lifted them up on our shoulders as unique and exquisitely trained heroes, then left them alone in the shadows of their past.

Uncertainty will never be far away for the Shooter. His government may have shut the door on him, but he is required to live inside the consequences of his former career.

One line from the film kept resonating in my head.

An actor playing a CIA station chief warns Maya about jihadi vengeance.

“Once you’re on their list,” he says, “you never get off.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the extent of the five-year health care benefits offered to cover veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Department of Veterans Affairs offers comprehensive health care to eligible veterans during that period, though not to their families. In light of this change, we have also revised an earlier passage in the story referring to the shooter’s post-service benefits. Also, the original version of this story did not include a few sentences that ran in the issue printed last week. They have now been restore

Taken From: http://www.esquire.com/features/man-who-shot-osama-bin-laden-0313

Navy SEAL lost health insurance after killing Osama bin Laden

Posted by Sarah Kliff on February 11, 2013 at 9:55 am

This email was cleaned by emailStripper, available for free from http://www.papercut.biz/emailStripper.htm

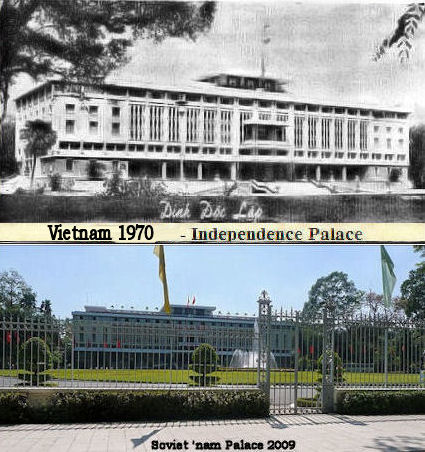

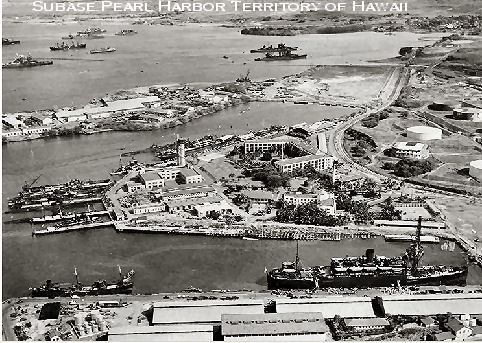

Subic Bay Phillipines and the Orient:

Subic Bay Phillipines and the Orient:

Corbis

Corbis

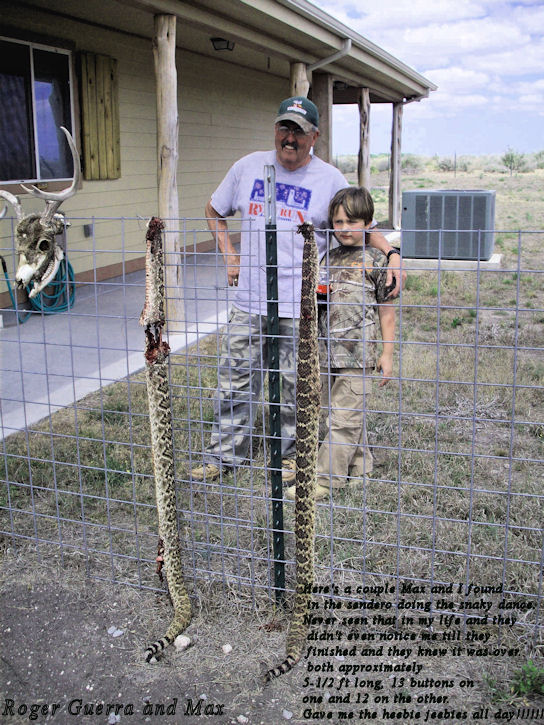

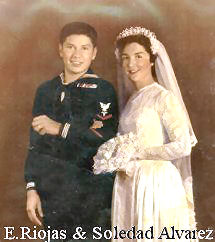

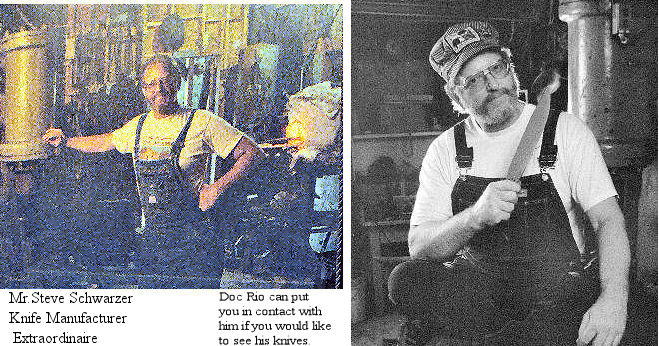

Ken & Son Bryce

Ken & Son Bryce