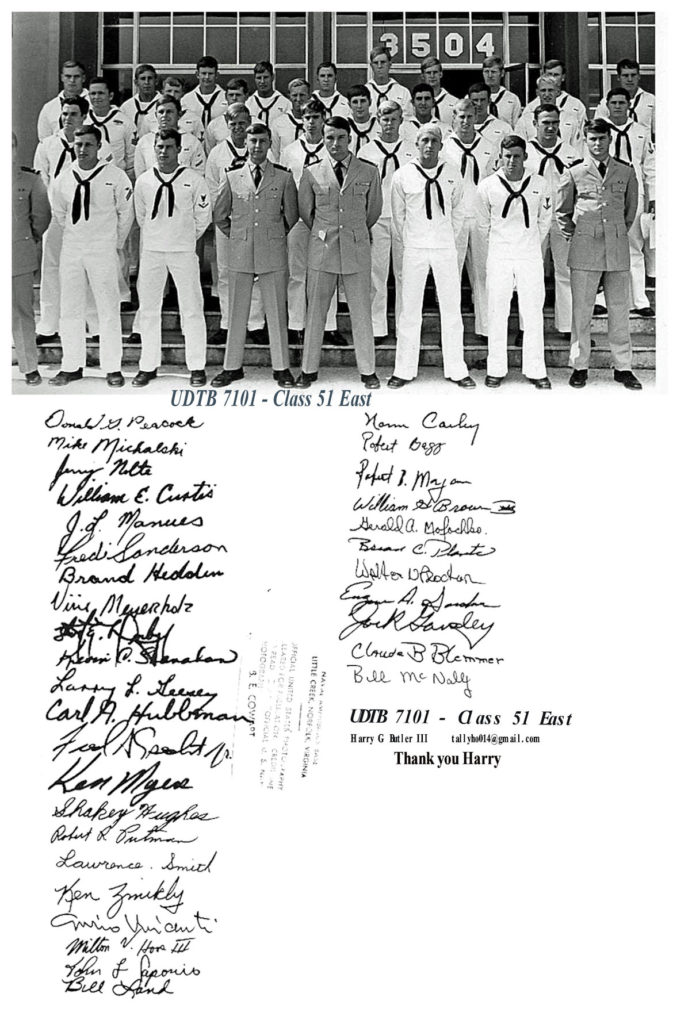

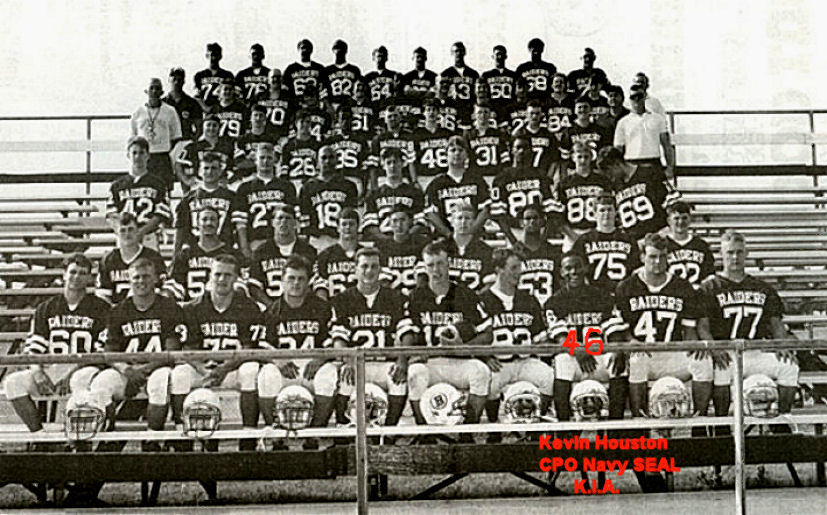

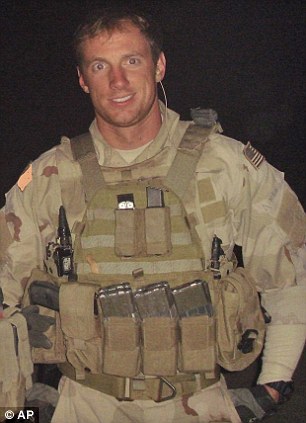

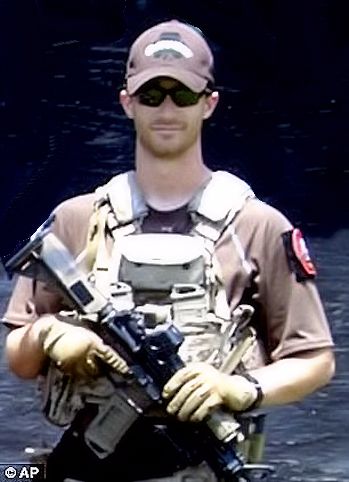

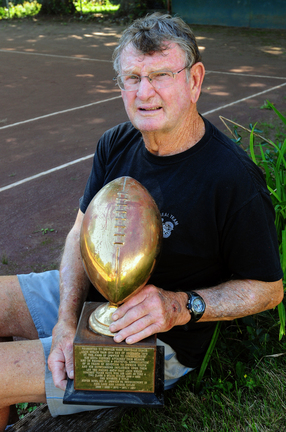

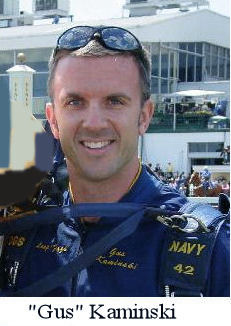

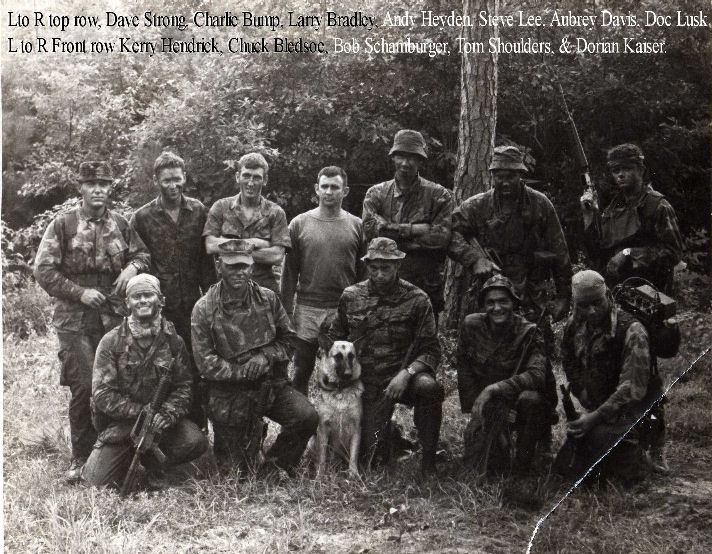

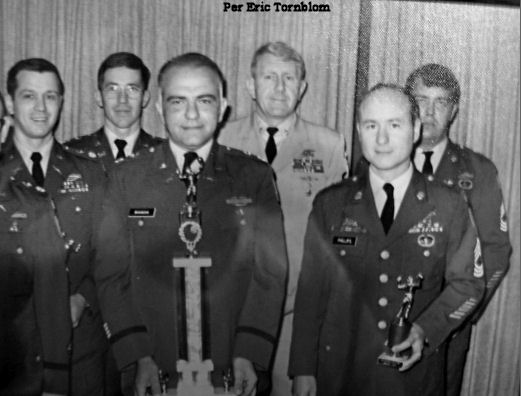

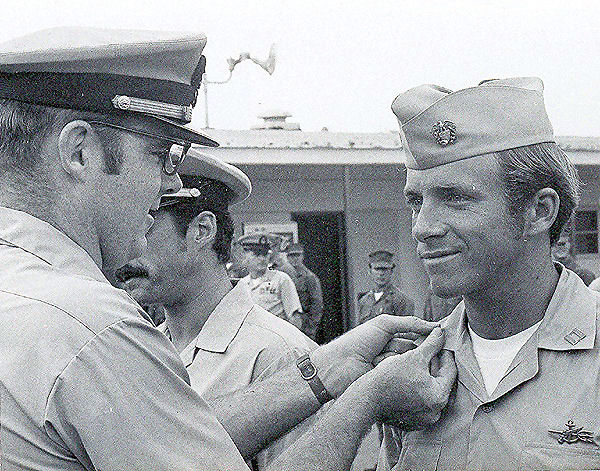

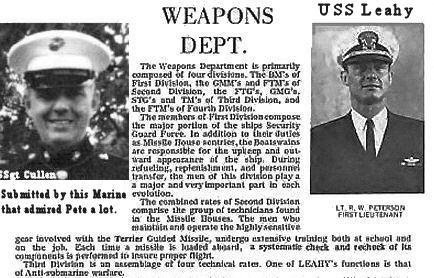

ST-1 C.O. promoting Slattery & Dry; note the UDT gold emblem on Slattery’s lt. breast !

SEAL Team One’s commanding officer promotes Slattery (right) and Dry (center) to lieutenant in 1971 during a ceremony at the team’s compound in Coronado, CA. U.S. Navy Photo courtesy of

26 Robert Dry

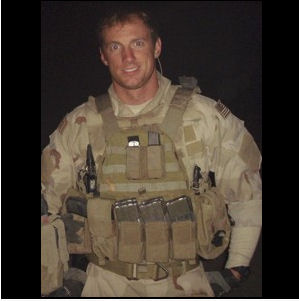

By Captain Michael G. Slattery ’68, USN (Ret.) A Tribute to a Classmate and SEAL Teammate

FEATURE But in true SEAL tradition, Spence would not quit. He knew he had to return as soon as possible to the submarine. He had information vital for a backup team preparing to launch a second attempt, and Spence was determined to see that they got it. During a secure communication with GRAYBACK’S commanding officer and the on-scene tactical commander, then-Commander John D. Chamberlain,Spence maintained that the information and experience he had just gained were vital to the success of future missions.

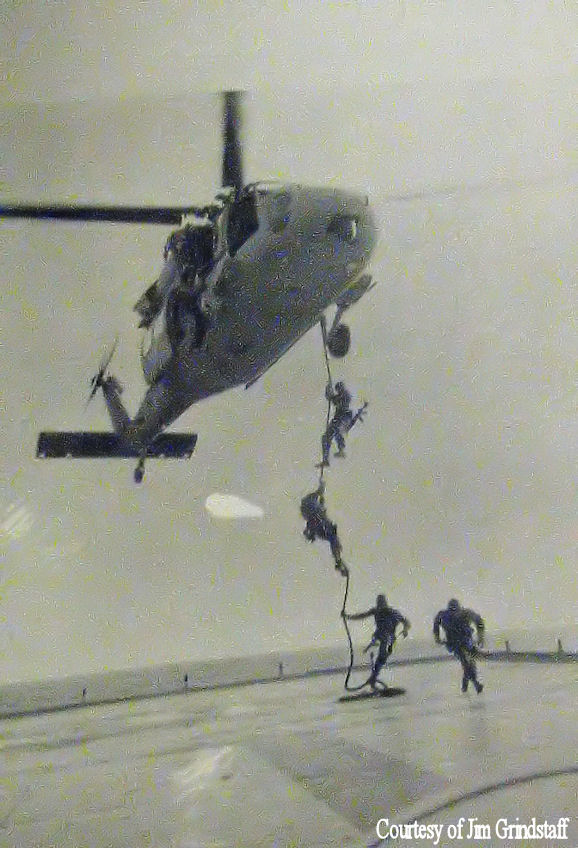

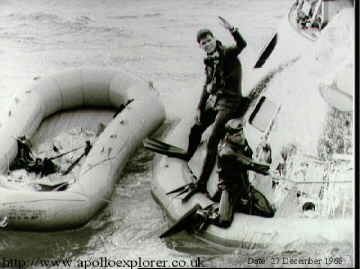

Accordingly, it was decided that the SEALs would be returned to GRAYBACK in the submarine’s operating area off the coast of North Vietnam.The SEALs would jump into the water near the submarine—a “helo cast” in SEAL parlance.The two SEALs and two UDT-11 SDV operators boarded the Navy helicopter for a rendezvous an hour before midnight. Beyond the challenge inherent with a nighttime cast, the attempted rendezvous was further complicated by the highly classified nature of the SEALs’mission—an operation so secret that the submarine had to remain submerged and undetected even by the U.S.Navy’s Seventh Fleet.

Its ships patrolled throughout this area of the Tonkin Gulf, and only a select few were aware of GRAYBACK and its Navy special warfare swimmers operating in their midst. After several unsuccessful passes, including one flown over North Vietnam’s coast, the helicopter pilot thought he had finally spotted the signal from the submarine. Spence and his men prepared to conduct the helo cast to link-up and lock-in to the sub.When told they were over their objective and given the signal to “drop,”Spence stepped out of the helo. The rest of the SEALs rapidly followed.

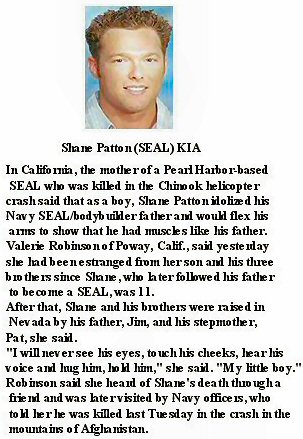

The helo was too high and fast for safe entry, and the jumpers hit the water hard. Spence was killed on impact, and the others injured—two seriously. Complicating the worsening chain of events,GRAYBACK was not in the immediate vicinity. The survivors were forced to tread water in the presence of enemy patrol boats until they were recovered by helicopter at daybreak. During the course of the night, one of theSEAL platoon’s most experienced combat veterans, then-Warrant Officer First Class Philip “Moki”Martin, found Spence’s body and held it for recovery. Spence would be the last SEAL to die in Vietnam.

Because his death was not specifically caused by enemy fire, and therefore, according to the cover story, simply a tragic mishap, it was classified as “accidental.” Besides the potential political fallout during the waning years of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, disclosing the highly classified nature of the operation that surrounded his death would put similar future POWrescue attempts at risk. But the risk to Spence and his fellow SEALs during that particularly dangerous operation was from more than just the looming threat of hostile fire.

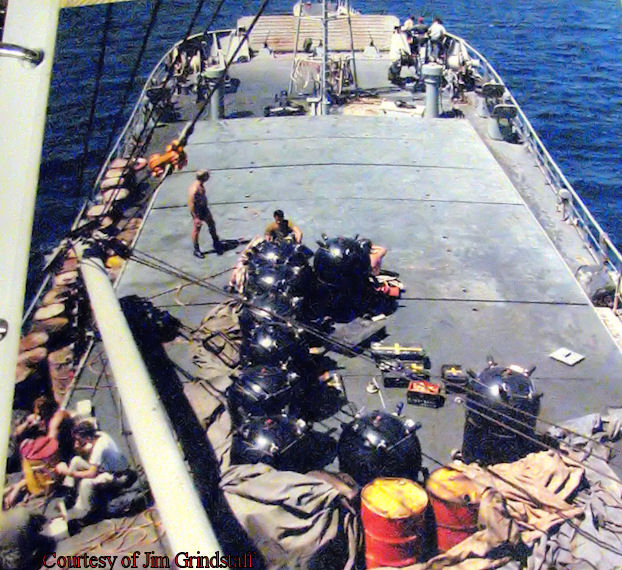

Several treacherous operational hazards were encountered throughout the entire operation’s full mission profile.And although certain aspects of his mission still remain classified, the risks included the night underwater lock out and launch from the submarine GRAYBACK; the longhours of submerged transit through enemy patrolled waters to the target area in an unproven, free-flooding SDV; the strong tidal current and sea state that made mission success problematic and ultimately forced the SEALs to tow the SDV seaward for seven hours to prevent its capture; and the high risk of detection and engagement by aggressive enemy patrol boats that probed the coastal waters and extreme shallows of the northern Tonkin Gulf off North Vietnam.

Such mission uncertainties of SEAL operations go with the territory. Throughout the entire rescue attempt, Spence’s team needed to remainundetected—even by friendly forces.But if the enemy did detect the SEALs and forced them to return fire, it would have been merely one more mission event to overcome in a long and continuous sequence of one high-risk rescue operation. We didn’t know those details when we learned of Spence’s loss at morning quarters in SEAL Team One’s compound in Coronado back in June 1972.

All we knew was that a close friend and good teammate, an outstanding officer with tremendous potential,had been killed.So, on the night that we learned of his death, four of his closest teammates gathered once more at Coronado’s Chart House and asked for a table for five by the window. It was a nice spot—one that Spence surely would have approved of—overlooking Glorietta Bay and the lights of San Diego and the Coronado Bridge. Everyone around us that night seemed to know something exceptional was unfolding…and they gave our table a wide berth. In that private space we each retold stories about Spence and raised our glasses to the empty chair and separate place that we had made the waiter set—with teriyaki shrimp.

Epilogue: On 25 February 2008, in an award ceremony in Memorial Hall, Lieutenant M.Spence Dry,USN, was posthumously presented the Bronze Star Medal with Combat Distinguishing Device “for heroic achievement in connection with combat operations against the enemy.” Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter also approved the award of the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal with Combat Distinguishing Device for then-CWO Moki Martin for May 2008 29 heroic actions during that high-risk mission off the coast of North Vietnam more than 35 years ago.

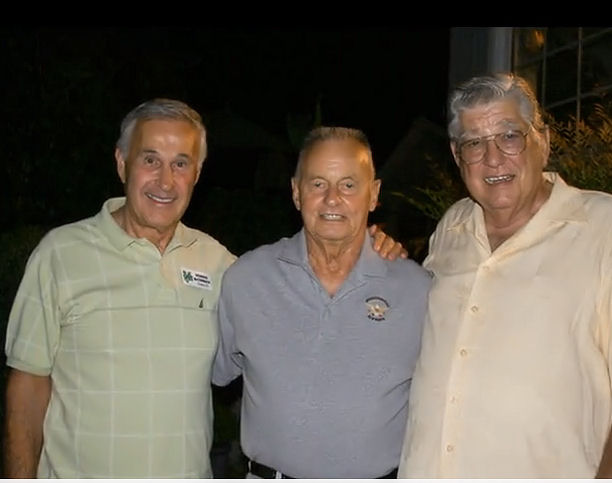

Following the award ceremony several of those who had attended that farewell dinner back in Coronado gathered that evening at the Annapolis Chart House for a very special reunion. Although it had been more than 35 years, our memories were still fresh and old stories flowed with the wine, and maybe a tear or two.a

This tribute by Captain Mike Slattery ’68,USN (Ret.), provided the basis for an article he co-authored with classmate Captain Gordon I.Peterson ’68,USN (Ret.),“Spence Dry—A SEAL’s Story,” published in the U.S.Naval Institute Proceedings in July 2005. Captain Slattery teaches History and Government at Campbell University in Buies Creek,NC.

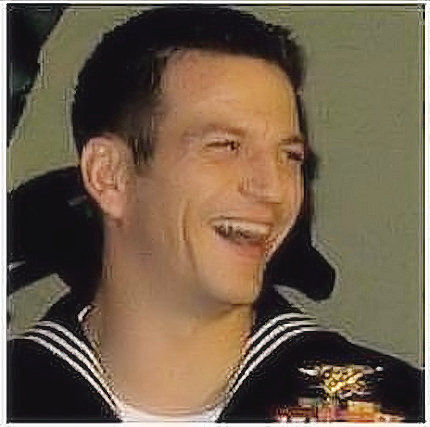

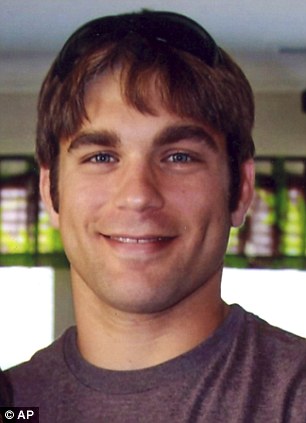

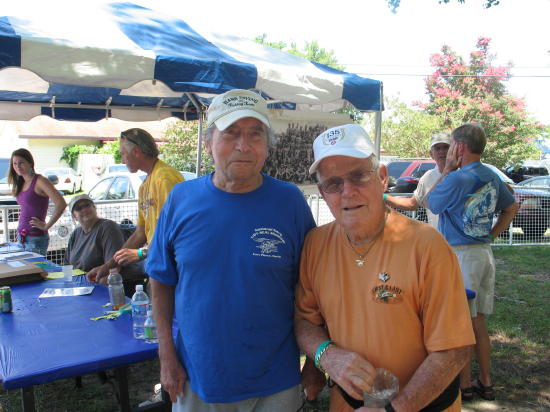

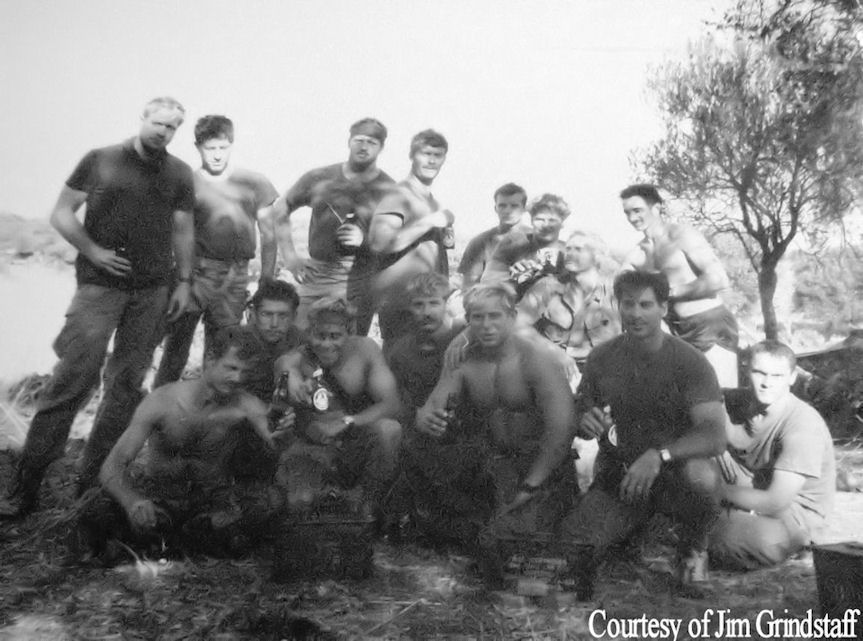

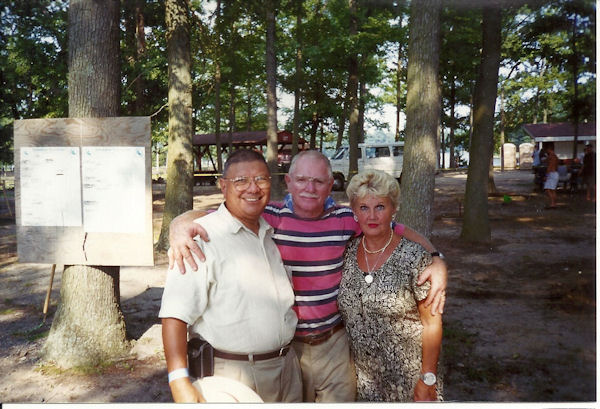

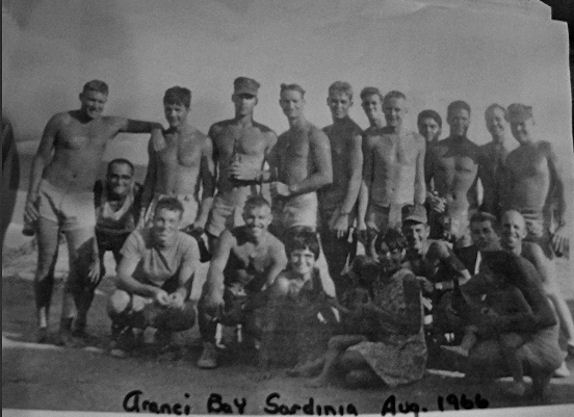

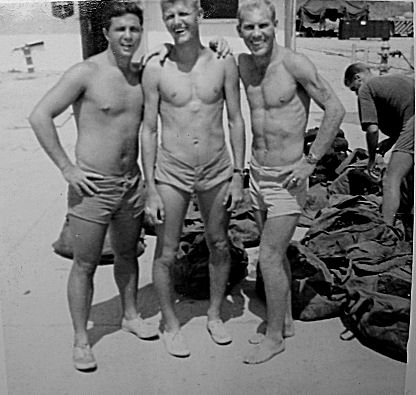

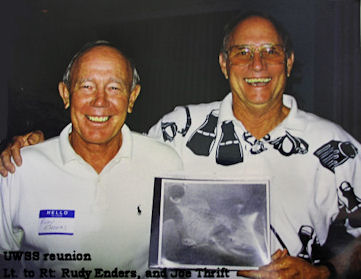

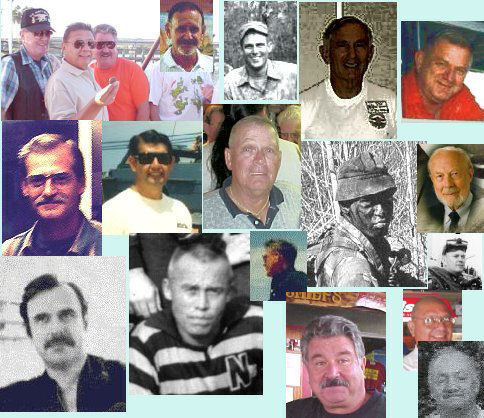

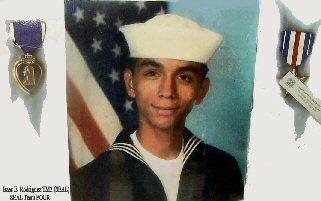

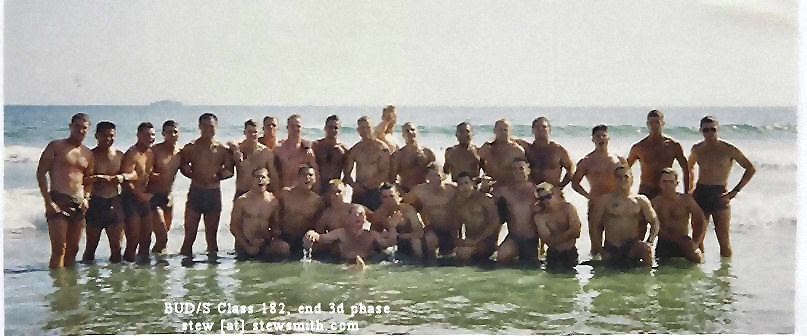

Lt – Rt: Mike Slattery, Jim Hoover,

Spence Dry, Jerry Fletcher, Mike Cadden

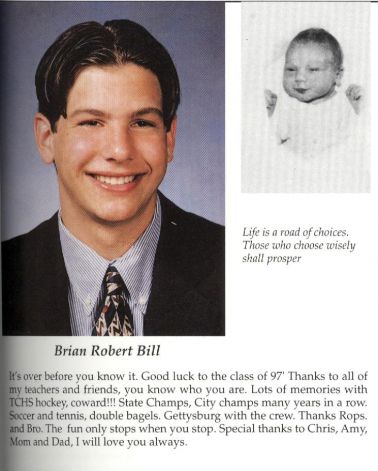

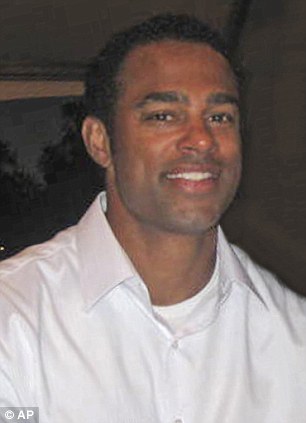

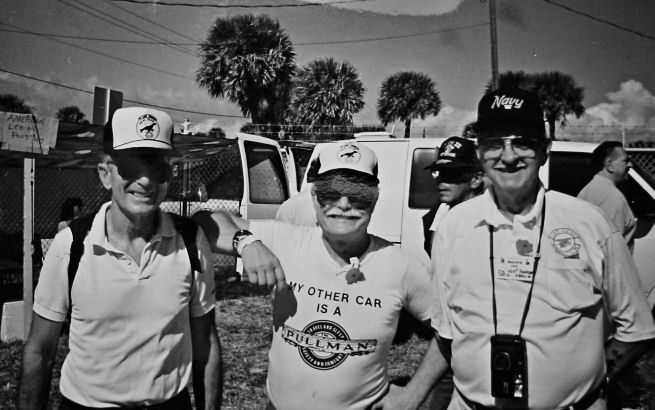

The five officers of BUD/S class 56 taken at the ceremony, from L to R: Captain Mike Slattery ’68, USN (Ret.); Lieutenant Commander Jim Hoover, USNR (Ret.); Lieutenant Spence Dry ’68, USN (photo); Commander Jerry Fletcher, USN (Ret.) and Lieutenant Commander Mike Cadden, USNR (Ret.).

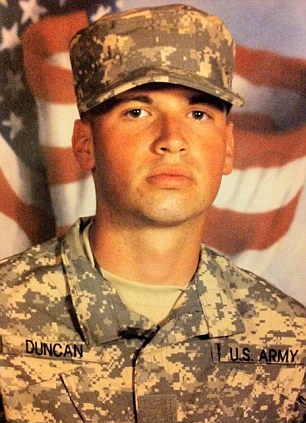

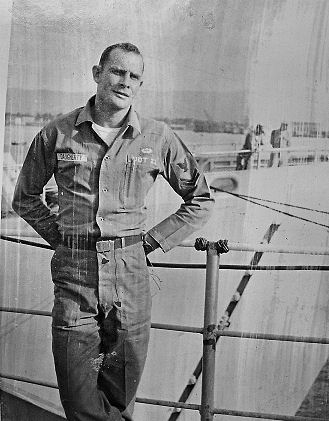

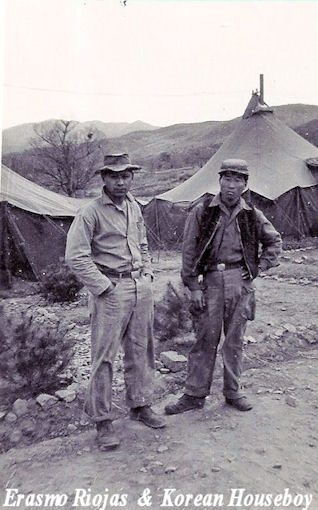

Michael G. Slattery LT. & M. Spence

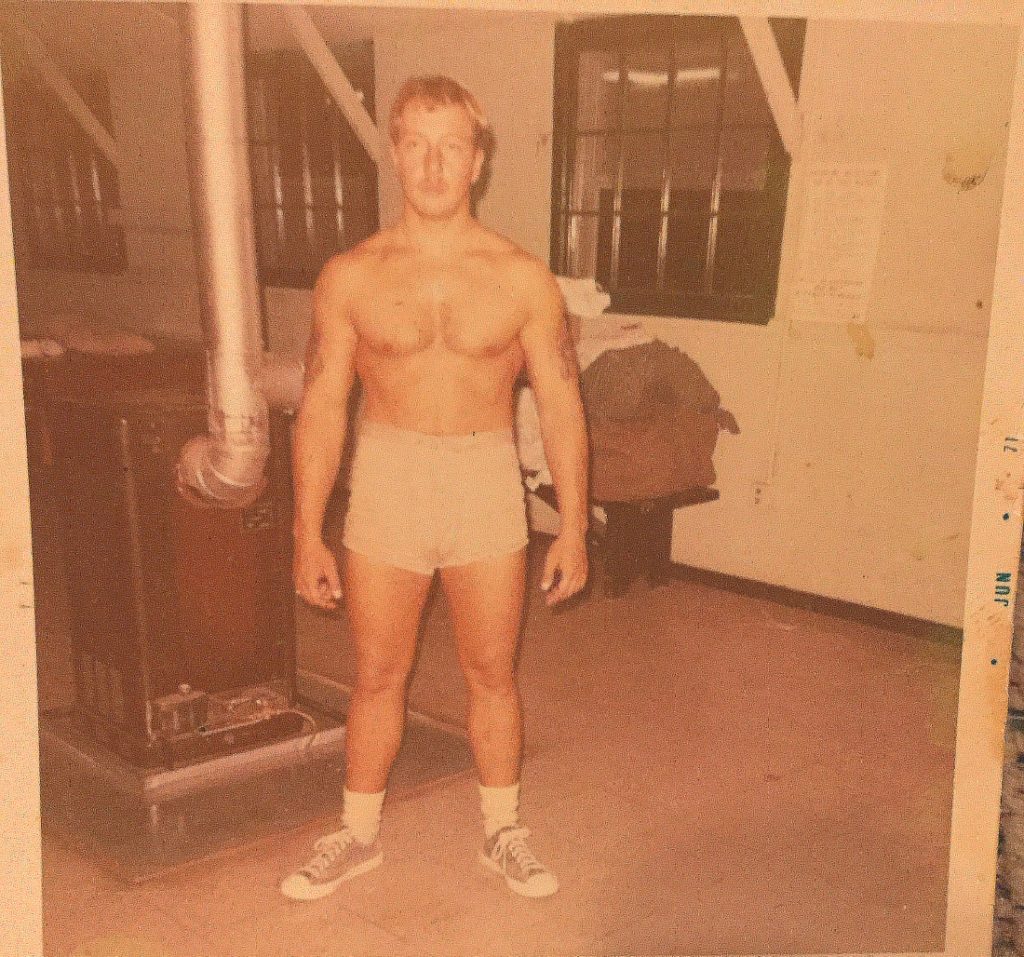

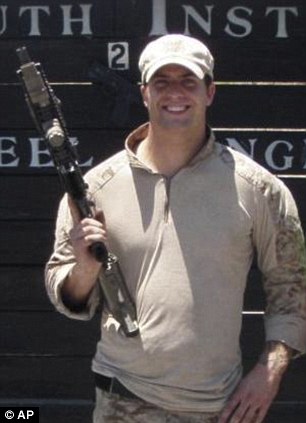

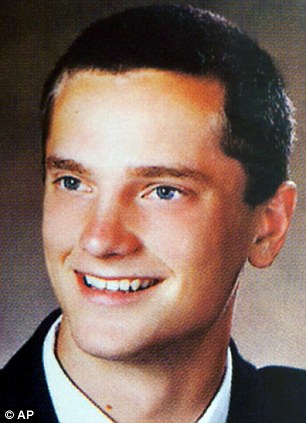

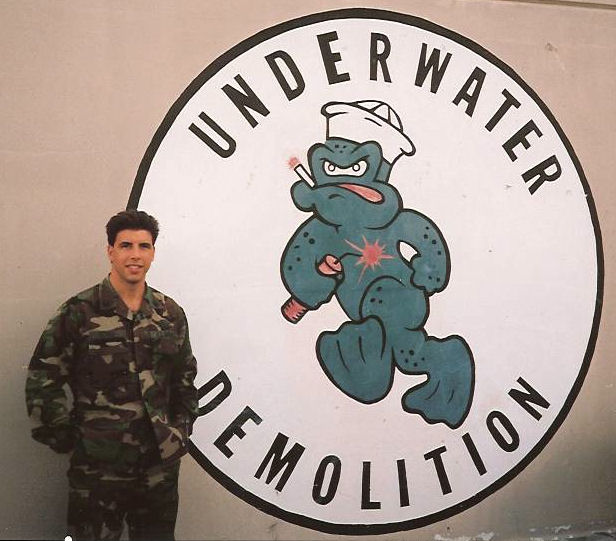

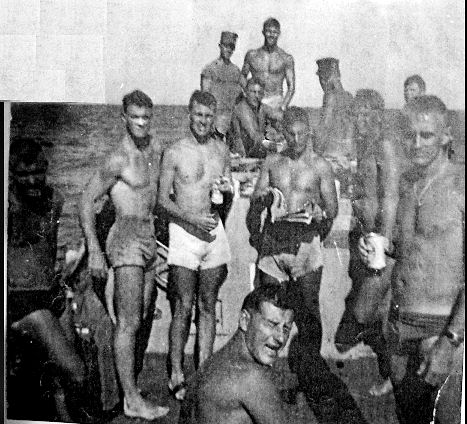

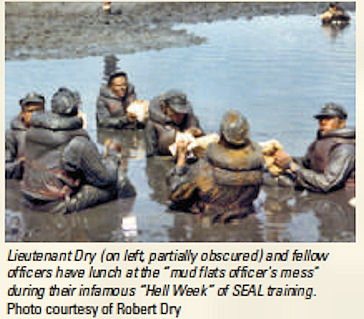

Then-Lieutenants (junior grade) Michael G. Slattery (left) and M. Spence Dry following the completion of “Hell Week” during Basic UDT/SEAL (BUD/S) Training. Photo courtesy of Robert Dry May 2008 27 Photo by Spence Cadden

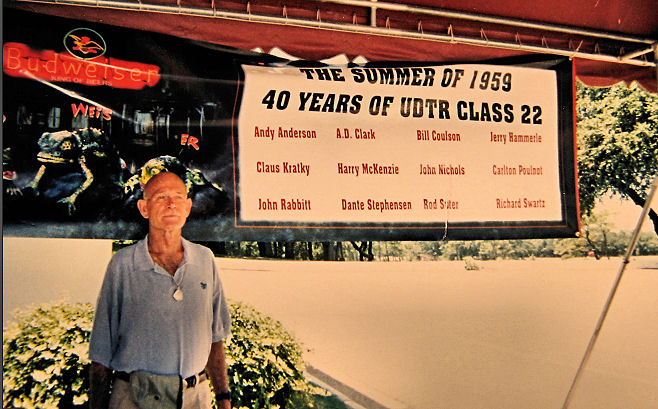

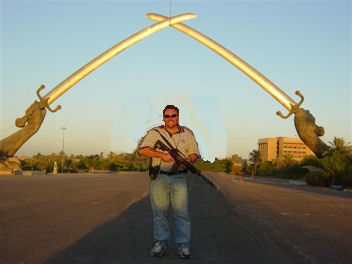

Lorimar Group – Mike Johnson