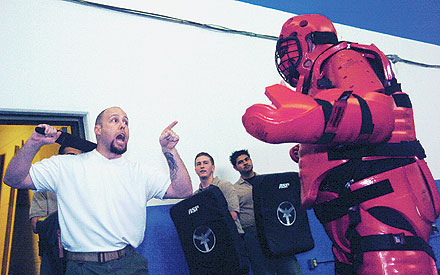

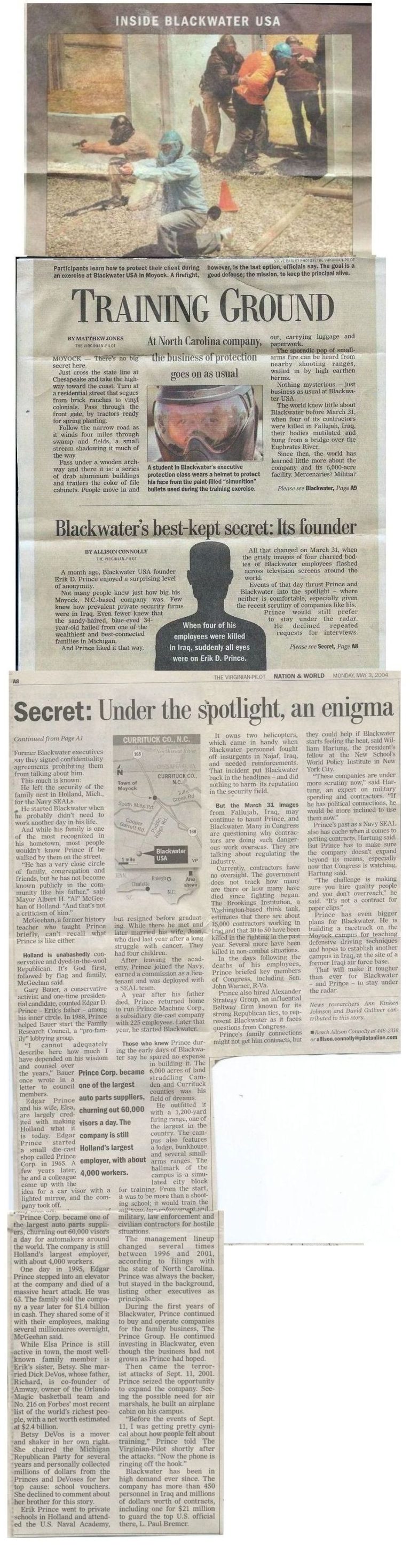

In 1997, Erik Prince founded Blackwater USA, expanding the family’s Christian conservative empire into private security and war for hire. Erik is a former U.S. Navy SEAL and son of the late billionaire automotive parts supplier, Edgar. (In a Q&A published by the Virginian-Pilot on July 24, Erik noted some of his father’s less successful ideas, including a sock drawer light and an automated ham de-boning device.)

The elder Prince was widely known for his close association with anti-choice crusader Gary Bauer. Bauer was a domestic policy advisor in the Reagan White House before succeeding Jerry Regier (a former Reagan official, as well) for the leadership role of the Family Research Council (FRC) in 1988. With Edgar’s help, Bauer put the FRC on the map. (When Edgar died in 1995, the company was sold for $1.4 billion.)

Erik’s sister Elizabeth, commonly referred to as Betsy, was the head of the Michigan Republican Party until early 2005. She is also the former finance chairwoman for the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC). She married Dick DeVos, the son of billionaire Amway co-founder (now under the name Alticor), Richard DeVos. Forbes ranked DeVos as the 121st richest person in the world in 2003 with an estimated net worth of $1.7 billion.

Under DeVos’ tutelage, Amway has donated roughly $7.5 million to Republican candidates since 1990. The contribution-tracking website, NewsMeat, lists personal campaign donations from DeVos; since February 1979, he has donated over $650,000 to Republicans, over $2 million to “special interests” and one lone contribution to a Democrat, Joe Torsella, in 2003.

Richard and his wife Helen operate the Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation and are known to have associations or donated to right-wing groups such as Focus on the Family, the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation.

Dick and Betsy DeVos donate huge sums of money to Republican candidates and causes. In the 2004 cycle, the couple ranked fifth among the highest political donors with $981,846 to Republicans. In fact, from 1990 through 2006, the couple donated $2,491,270 to Republicans with only $1,000 going to Democrats back in 1992.

The Grand Rapids Press reported July 9:

Since 1999, DeVos, his wife, Betsy, and their immediate family have poured at least $7 million into expanding school choice — vouchers, tuition tax credits and charter schools — and promoting candidates who back those causes.

In 2000, the family headed the campaign to legalize school vouchers in Michigan, raising big money and donating plenty as well. The initiative failed to pass.

This election cycle, the family is back at it again. But this time, Dick is running for the Republican Party’s nomination for Michigan Governor. His campaign chairman is David Brandon, chief executive of Domino’s Pizza and major Republican donor. Brandon has given over $100,000 to GOP candidates since 1987. (Side note: The founder of Domino’s Pizza, Thomas Monaghan, broke ground on the Ave Maria, Florida township, complete with its own university and strict Catholic-based laws.)

As for Erik, he started in Republican politics early, making his first donation — $15,000 — to the GOP at the age of nineteen. (At 19, I was $10,000 in financial aid debt and eating Ramen quite frequently.) Since 1989, Prince has donated over $151,250 to Republicans.

According to The News & Observer, Prince was among the first interns at the Family Research Council and interned for President George H.W. Bush for six months. (It is reasonable to suggest that, through his father’s Reagan-era connections, he was able to get the position.) He campaign for Patrick Buchanan’s Republican primary challenge to Bush in 1992, possibly because he “saw a lot of things I didn’t agree with — homosexual groups being invited in, the budget agreement, the Clean Air Act, those kind of bills. I think the administration has been indifferent to a lot of conservative concerns,” he told the Grand Rapids Press in early 1992.

That far-left lefty leftist Bush really showed his true colors, didn’t he? Actually talking with gays in the White House? Heavens to Betsy!

It should also be noted that Erik served as a defense analyst for tainted Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-California). Rohrabacher was a special assistant to Reagan before being elected to Congress in 1988, and has a chronicled involvement in the scandal of disgraced Republican lobbyist, Jack Abramoff.

Erik was a volunteer firefighter and enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1992, joining the elite SEALs and operating with the SEAL Team 8 in Norfolk, Virginia. Due to personal reasons, his military career was cut short, bowing out in 1996. At the age of twenty-seven, he founded Blackwater USA.

He is a board member of the Christian Freedom International, “a nonprofit group dedicated to helping persecuted Christians around the world,” reported the Virginian-Pilot on July 24, 2006. As of April 2005, among the list of “directors” for CFI is Robert Reilly, the former director of the Voice of America (VOA), who was criticized for being “too ideological.” (The New York Times reported on the ideological bent in October 2001. Subscription required.) After Reilly resigned “abruptly” from the VOA, the April 21, 2003 edition of the Christian Science Monitor, it was reported that he now heads the Pentagon’s broadcasting efforts in Iraq.

Prince is associated with a number of other companies. In addition to Blackwater, he is affiliated with Bering Truck Distribution, Phase One Ltd., the Prince Group (who hired the former Defense Department Inspector General, Joseph E. Schmitz) and Prince Household L.L.C. He has associations with the Christian Solidarity International (CSI) and Institute of World Politics, a national security organization that teaches graduate diplomats and offers two Masters degree programs. He is also listed among the forty Board of Trustees for the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum with Senator John McCain.

Presidential Airways, whose parent company Presidential Airways, Inc. and its sister company, Aviation Worldwide Services (AWS), are owned by Blackwater, and based in Melbourne, Florida. It received a $2.43 million contract from the Department of Defense to provide “aircraft supports,” in February 2006. Late last year, Washington Post reporter Dana Priest revealed a network of secret CIA prisons in Eastern Europe; she received a Pulitzer Prize for her work. It turns out, according to independent media sources, AWS and Presidential were both involved in the chartered flights.

Erik and his politically-active extended family are enablers of the Republican political elite and are reaping the benefits in return. Specifically, Erik is a war profiteer through his private security company’s paid warriors. Beholden to nobody but the almighty dollar, these mercenaries are increasingly tasked with operations that were formerly conducted by uniformed U.S. military personnel.

Which do you trust?

Erik is notorious for his media-shy demeanor and preference to stay out of the lime light. What better way to send him a message about his company’s practices in Iraq than by casting him under the spotlight he seeks to avoid. Please contact us with any insights into this otherwise secretive and reclusive war whore.

Blackwater USA Headquarters

850 Puddin Ridge Road

Moyock, North Carolina 27958 [source: British American Security Information Council (BASIC) Research Report, September 2004: