On March 17, 1961 the author was frightened by an aggressive carcharhinid of at least 8 feet in length believed at the time to be springeri, but which could have been galapagensis. The shark, which was lacking the outer part of the upper lobe of its caudal fin, passed nearby at a depth of 90 feet in the clear water on the north shore of Tobago, British Virgin Islands. It made a broad circle as the author rose in the water toward the safety of a vessel overhead, and then it rushed upward. Acting on the belief that the usual first rea~ction of an animal which is attacked is to retreat, an overt movement was made in the direction of the shark, and it veered off. The boat was reached before the shark returned.

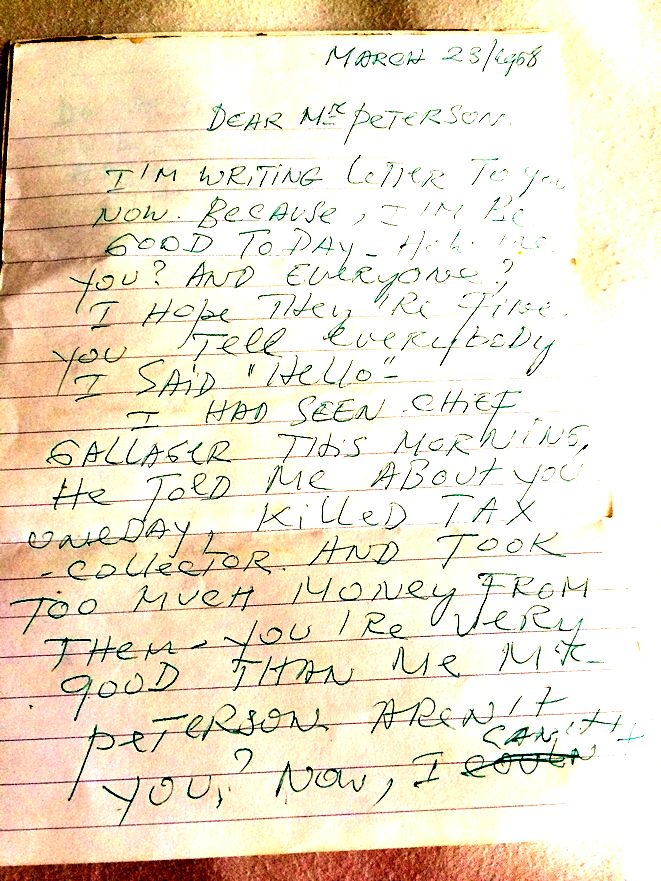

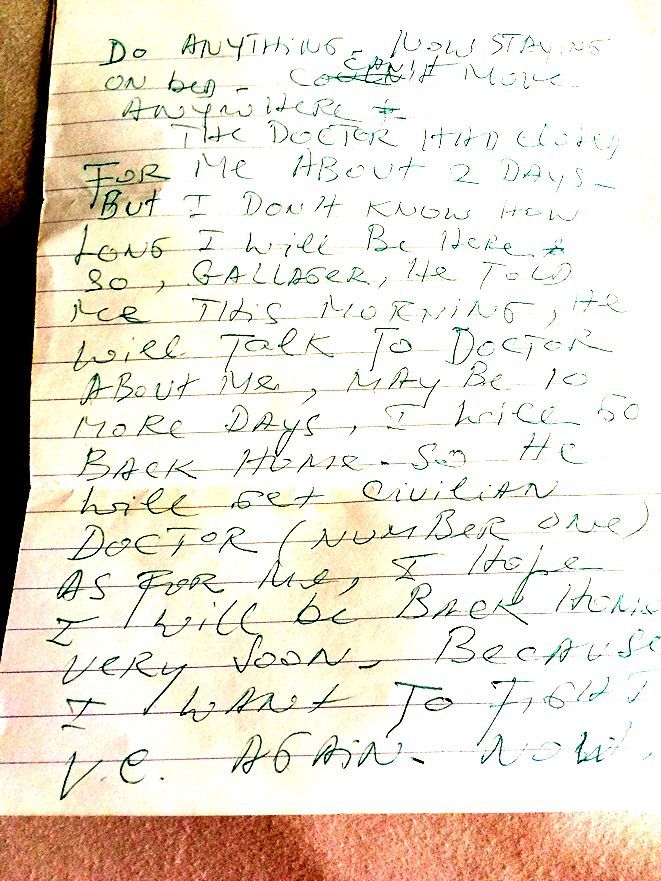

Email 10Jan2014

From: Dante Stephensen

Yes, Doc, I knew him (he was 2 or 3 classes behind me and an excellent competitive college swimmer.

1. He decided to swim the ½ mile+ or so across shallow Magens Bay, St. Thomas as his girlfriend walked the beach to meet him on the other side. But more important, this was the finest largest most popular beach in all of St. T. and the locals understandably were both horrified & petrified.

2. This was the islands first known shark death attack and the victim was a frogman…unheard of. The fear on the island was intense. They worried that tourism might take a big blow.

3. His date actually walked into the water to pull him ashore and the shark tugged and dragged him back out into deeper water. By this time he was likely unconscious or dead.

4. So I suggested we set some traps and was laughed at. Point is, we might get lucky. We knew the shark was large, about 11 feet long. I summarized that this might be an older shark who could not fend for himself in the deep ocean and came to shallow water looking for a free meal. Turns out I was correct. He is also of an unknown breed which I cannot pronounce.

5. So I gathered some volunteers, those who did not volunteer thought I was nuts. Our skipper finally gave in and gave us two LCPLs to use. He stipulated that I be the OIC of this silly mission…

6. We worked all night preparing 55 gallon drums, rancid meat, shark hooks, etc.

7. Next morning we took the long trip around the island to Magens Bay. Yes it was hot out.

8. I ran my command post from the top of a hill so I could see the whole shallow clear bay.

9. All day we thought we saw a large figure swimming, but no one was sure; the water was both clear and shallow. We were all getting tired since no 55 gallon drum was seen bouncing.

10. The day was now over, all wanted to go have a beer, but I said no, not until we check each barrel. Since no one noticed one bobbing, my guys said I was nuts and resisted, but I held firm.

11. One by one each shark line at each barrel was examined.

a. Barrel 1. The shark hook was straightened out and the rancid goat meat was gone. Wow.

b. Barrel 2, Same thing. We began to get excited. Maybe we weren’t nuts, after all.…

c. Barrel 3, nothing had been touched. Now it was getting depressing…until the next one.

d. Last barrel. We caught a shark, very tired from fighting the hook, he was shot and brought aboard one of the LCPLs. As yet, no one knew if we got the right shark. He was enormous.

12. We headed for our base on the other side of the island. I was told Geo. Wall cut open the 11 foot shark and found inside him a hand, an arm, a UDT watch, etc. Yes, we got the culprit…

13. The island relaxed and returned to normal.

14. Our doc. Ken Faust, stipulated the found parts belonged to Ens. Gibson, our missing Frogman.

Since this was the “first” shark occurrence for St. Thomas, someone is writing a book about it and called me for help, not knowing I was involved in the capture. And so it goes.

Your buddy, Dante

This email was cleaned by emailStripper, available for free from http://www.papercut.biz/emailStripper.htm

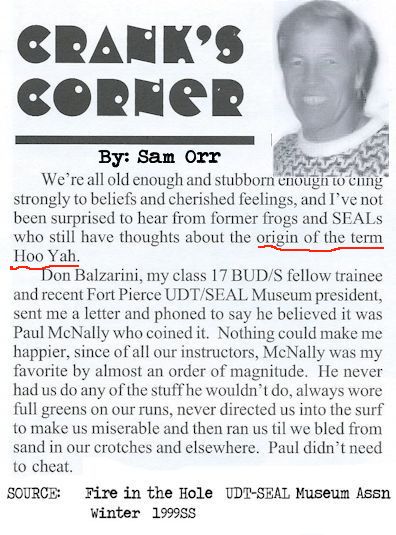

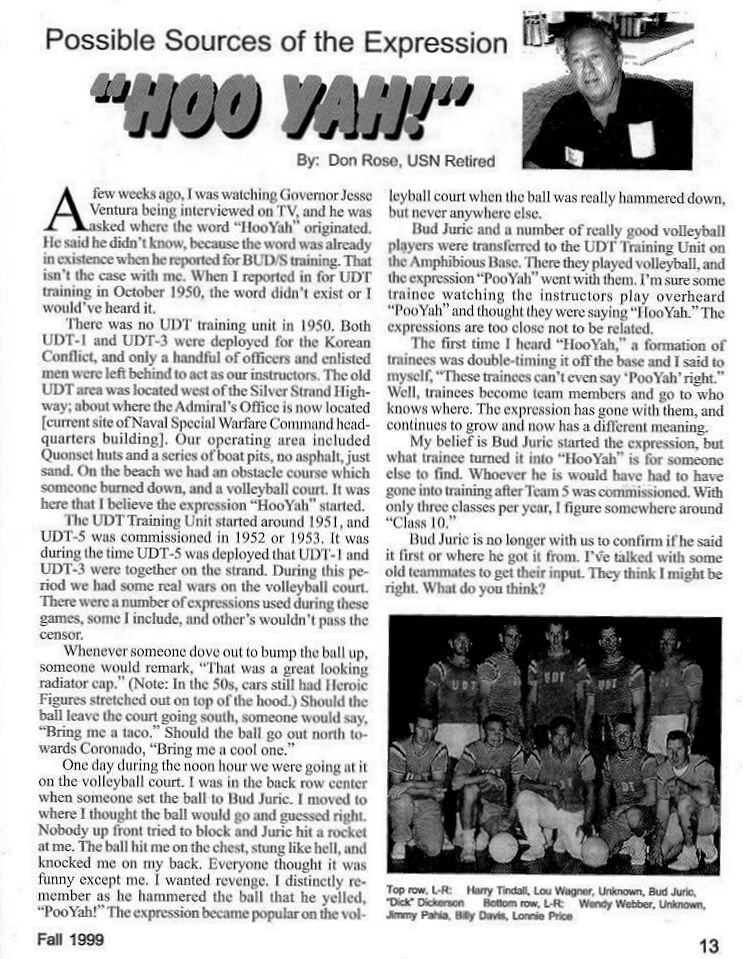

Hooyah! A shouted term used often in SEAL Training that means:

Hell Yeah!

Fuck off

Fuck you

OH SHIT, not again!

Yes Instructor

Not again

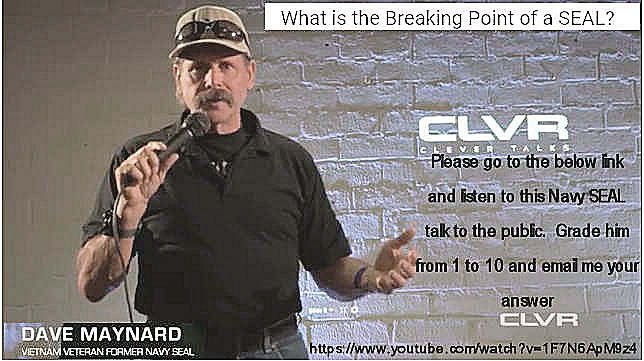

Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People:

Insights from Navy SEALs to the “Greatest Generation” Electronic copy available at: http://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=300072021025001067100092

1031121241130250050050040700180731181221170260911080221091091171030250241

230460081070650960100080141150170600930090000951090870060071070070220170

93095120093022089102093029003018126076087106028077104

124090124124004107091115082101&EXT=pdf IJEMH • Vol. 14, No. 2 • 2012 137International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. xxx-xxx © 2012 Chevron Publishing ISSN 1522-4821

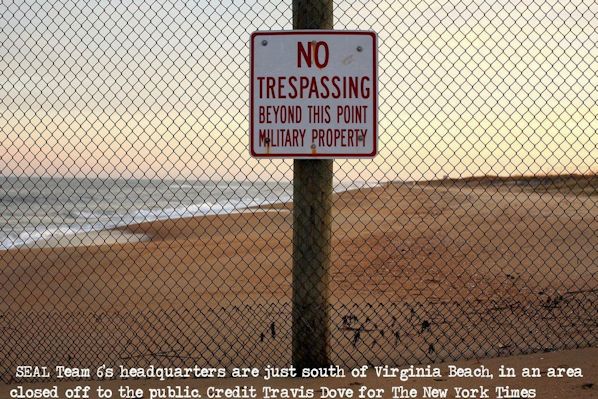

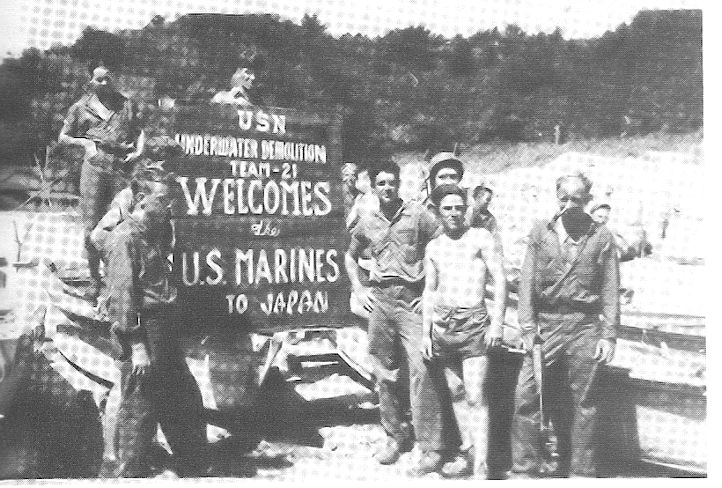

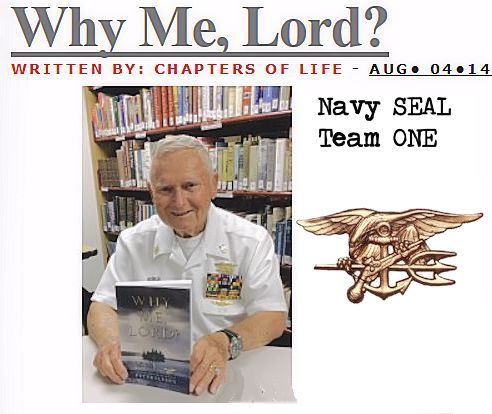

Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People: Insights from Navy SEALs to the “Greatest Generation”Abstract: Having reviewed investigative methods such as structural equation modeling, seminal manuals ofwar (von Clausewitz, 1976, rev.1984; Clavell, 1983), as well as individual interviews and focus groups with highly resilient people such as Navy SEALs, law enforcement professionals, and the “children of the GreatDepression” now commonly referred to as the “greatest generation,” we sought to discover the commonthemes, or characteristics, of highly resilient people. In this paper, we present our initial impressions that there exist seven important characteristics that seem to be associated with enhanced human resilience. [International Journal of Emergency mental Health, 2012, 14(2)] Key words: Resilience, Navy SEALS, Johns Hopkins Model of ResiliencyGratitude is extended to CAPT Don Hinsvark, MA, Underwater Demolition Team Eleven, Naval Reserve Naval Special Warfare Detachment 119, United States Navy (retired) for his personal support and valuable contributions to this paper.

Thanks, also, to Jacqueline Hinsvark for her help in concept formulation and refinement. George S. Everly, Jr., PhD, ABPP, serves on faculty at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

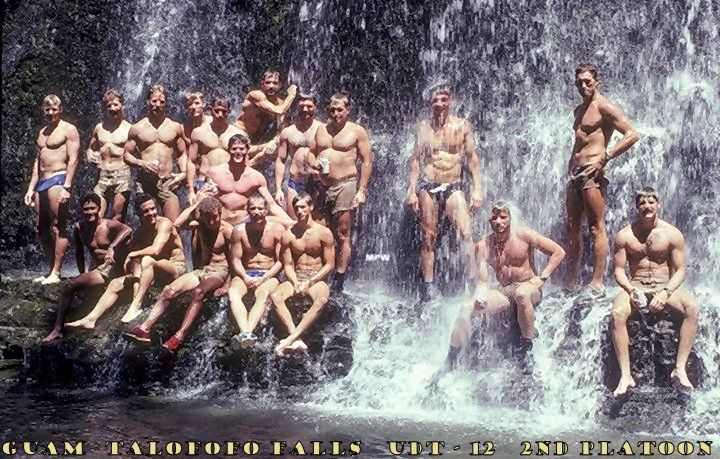

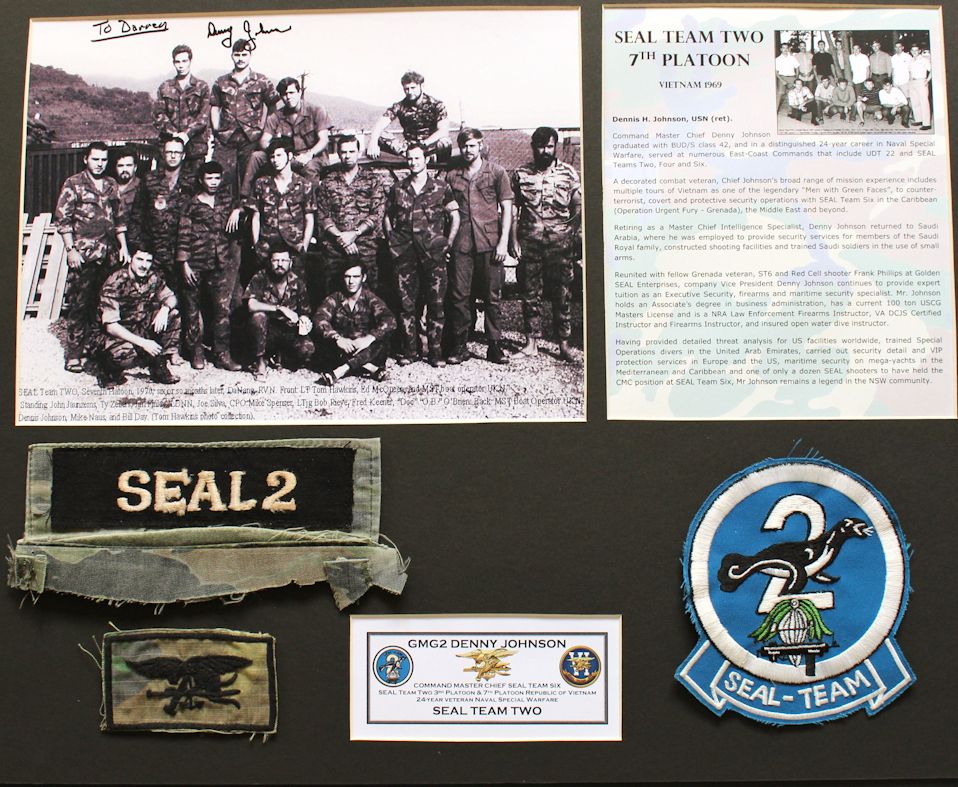

Dennis K. McCormack, Ph.D. served with Underwater Demolition Team Twelve, and SEAL Team One, United States Navy (retired). Douglas A Strouse, PhD is the President and CEO of Global Data, Inc in Towson, MD.

Correspondence regarding this article should be directed to geverly@jhsph.edu A review of current events reveals crisis in epidemic proportions. Political crises, not just in the United States, but in Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Italy, seem largely symptoms of a far more pervasive and malignant state of economic crisis. While crisis is becoming the norm, it is still anxiogenic.

From a community, or societal, perspective, crisis (or even the threat thereof) stifles innovation, is an impediment to investment, fosters a hording mentality, and is generally de-stabilizing. From a personal perspective crisis creates fear, unrest, and paralyzes inclinations to act, or leads to the opposite course, ie, impulsive, often regretful, actions largely because it threatens a core human need – the need for safety. The resultant toxic environment may erode organizational, community, and personal health. As dismal as this might sound, not every organization, community, or person is adversely affected by the toxicity of uncertainty and manifest crisis. Some individuals seem resilient in such George S. Everly, Jr The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Dennis K. McCormack Underwater Demolition Team TWELVE , SEAL Team ONE Supervisory Clinical Psychologist (Ret.) Douglas A Strouse Global Data, Inc Towson, MD Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2118935

138 Everly, McCormack, Strouse

• Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People circumstances; thus they are minimally affected. Others manifest such resilience that they seem actually to prosper in adversity. In times of prosperity, there is little motivation to study human resilience, but during times of uncertainty, crisis, and adversity the motivation is substantial. In previous publications

(Everly, 2009; Everly, etal, 2010), we have written about the elements of what we refer to as a resilient culture.Here we turn our attention to the individual. Thus, having reviewed investigative methods such as structural equation modeling, seminal manuals of war (von Clausewitz, 1976, rev.1984; Clavell, 1983), as well as individual interviews and focus groups with highly resilient people such as Navy SEALs, law enforcement professionals, and the children of the Great Depression, we present our initial impressions that there exist seven important characteristics that seem to be associated with enhanced human resilience. Resilience Defined Human resilience may be thought of as the ability to positively adapt to and/or rebound from significant adversity and distress. Bonnano (2004) defines resilience as the ability of adults to maintain relatively stable and healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning after having been exposed to potentially disruptive or traumatic events. Bonnano suggests that factors such as hardiness, self-enhancement, repressive coping (emotional dissociation), and positive emotions may under gird effective resilience In a review of runaway children who showed remarkable resilience, key factors emerged as protective according to William, Lindsey, Kurtz, and Jarvis (2001). These protective factors include:

• determination and persistence,• an optimistic orientation to problem-solving,• ability to find purpose in life, and• caring for oneself.According to The Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, Fostering Resiliency [available online: http://www. nwrel.org/pirc/hot9.html, children who develop competence, despite adversity and difficult conditions while growing up, appear to share the following qualities:

• a sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy,• an action oriented approach to obstacles or challenges,• the ability to see an obstacle as a problem that can be engaged, changed, overcome, or at least endured, • reasonable persistence, with an ability to know when “enough is enough,” and• flexible problem-solving and stress management tactics. Haglund, Cooper, Southwick, and Charney (2007) provide one of the most succinct analyses of the various components of resilience. They identify six primary factors that may protect against and aid in recovery from extreme or traumatic stress:

• actively facing fears and trying to solve problems,

• regular physical exercise,

• optimism,

• following a moral compass,

• promoting social support, nurturing friendships, and seeking role models, and

• being open minded and flexible in the way one thinks about problems, or avoiding rigid and dogmatic thinking. The Johns Hopkins Model Of Resiliency One integrative model contributing heuristic value to the construct of resilience is the Johns Hopkins Model of Resistance, Resilience, and Recovery (henceforth, the Hopkins Model). The Hopkins model served to advance the field by recognizing the importance of putting resilience on a continuum, and by separating out the notion of protective immunity from the notion of resilience as a form of rebound

(Kaminsky, McCabe, Langlieb, & Everly, 2007; Nucifora, Langlieb, Siegal, Everly, & Kaminsky, 2007; Nucifora, Hall, & Everly, 2011). The Hopkins model describes resistanceas the ability to withstand manifestations of clinical distress, impairment, or dysfunction associated with critical incidents, terrorism, and even mass disasters.

One could think of resistance as a form of “psychological immunity todistress and dysfunction” (Nucifora et al., p. S34). Resilience,in this model, refers to the ability to rapidly and effectively rebound from psychological and/or behavioral perturbations associated with critical incidents, terrorism, and even mass disasters (Kaminsky, McCabe, Langlieb, & Everly, 2007). IJEMH • Vol. 14, No. 2 • 2012 139Finally, recovery refers to observed improvement following the application of treatment and rehabilitative procedures. Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People In an effort to integrate previous theory and research in human resilience, we offer a distillation of findings in an effort to better inform the enhancement of human resilience. We believe that the defining elements of human resilience reside in seven core characteristics, all of which can be learned

(Everly, 2009, Everly, Strouse, & Everly, 2010, Everly & Links, in press):

• présence d’esprit: calm, innovative, non-dogmaticthinking,

• decisive action,• tenacity,• interpersonal connectedness,

• honesty,

• self-control, and

• optimism and a positive perspective on life.

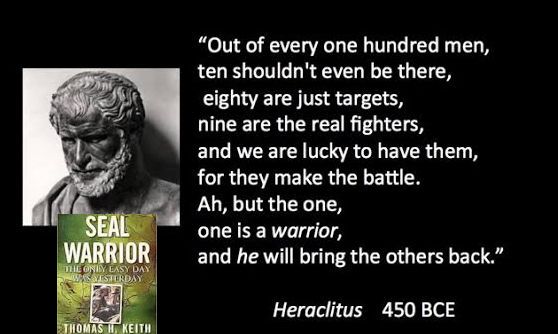

Présence d’esprit, or calm, innovative, non-dogmatic thinking, is an essential element in resilience. Having the presence of mind to think in a calm, rational manner, especially under stress is rare. The ability to see old problems from a new perspective is key to overcoming hindrances that stifle others. Sometimes referred to as “out of the box” thinking, innovative thinking is characterized by highly flexible, nondogmatic cognitive processes. Such cognitive processing can result in a new level of decision-making efficacy. The key platform upon which innovative thinking rests is the belief that a solution can always be found. The SEAL Ethos states that, “We demand discipline. We expect innovation. The lives of my teammates and the success of the mission depend on me, my technical skill, tactical proficiency, and attention to detail.

My training is never complete” (McCormack, in press). Navy SEALs embody many qualities which enhance their ability to succeed in the most arduous of situations. Innovation is perhaps one of the most powerful characteristics which may well define a crucial element in determining success over failure in any given situation. Change is inevitable, and the more predisposed one is to employ creative thinking in those critical moments when decisions made make the difference between life or death, the better position one is in to cope effectively and succeed. Innovation is a necessary ingredient of a SEAL’s personal arsenal. Innovation is synonymous with a solution-focused process leading to the implementation of decisions which will help ensure success. The essential focus is not concentrating on what is wrong, per se, but rather, having defined the problem, the focus is on finding a novel solution. Success as a team requires maximum participation of team members in this creative approach to problem solving. The pressure of problem-solving is often disabling, in short, the tyranny of the decision proves disabling to all but the most resilient. Once a decision has been reached, it is essential to act decisively. Many people wait for the “moment of absolute certainty.” Sadly the moment of absolute certainty seldom comes, or when it does, its often too late

. The English proverb, “He who hesitates is lost,” seems apropos in this context. The hesitancy that typifies non-resilient decision-making is often the fear of making a mistake, or failing. The corollary to decisive action, however is the necessity to take responsibility for one’s actions. Taking responsibility is sometimes difficult, especially if the action leads to an undesirable outcome. However, highly resilient people are often the first to take responsibility because they see that as the first step toward resolution and subsequent success. Sometimes, making a decision and acting on it in a timely manner is still not enough to warrant being considered resilient. Tenacity is essential. Great American success stories are replete with the theme of tenacity. In many cases it was not the genius that predicted success, it was the tenacity. Take the case of the electric light bulb. The first electric light was invented in 1800 by Humphrey Davy, an English scientist. He successfully electrified a carbon filament with a battery. Unfortunately, the filament burned out too quickly to have practical value. In 1879, Thomas Edison discovered that a carbon cotton filament in an oxygen-free glass bulb not only glowed but would glow for up to 40 hours. This new bulb required relatively low levels of electricity and could be produced for a large market. With further time, Edison created a bulb that could glow for over 1200 hours. And what was the difference between Davy on one hand and Edison on the other? Edison persevered in his testing until he found the right combination of filament and bulb. But, according to Edison himself, it required over 6000 failed experiments to arrive at the right combination.

140 Everly, McCormack, Strouse

• Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People As Abraham Lincoln learned, numerous failures often precede remarkable victories. In 1833 Lincoln failed in business, but he was elected to the Illinois state legislature in 1834. In 1835, he lost his “sweetheart.” In 1836 he suffered a “nervous breakdown.” In 1838 he was re-elected to Illinois legislature. In 1843, Lincoln was defeated for a congressional nomination, but was elected in 1846. In 1848, he lost re-nomination. In 1854, Lincoln was defeated in his run for the U.S. Senate and then defeated for nomination for Vice President in 1856. In 1858, Lincoln was again defeated for U.S. Senate. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected 16th President of the United States.

Finally, On July 4, 1863, in the little town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, President Abraham Lincoln delivered in about two and one half minutes one of the greatest presentations of American oratory, his Gettysburg Address, wherein his words resound with tenacity and optimism. Interpersonal connectedness and support may be the single most powerful predictor of human resilience. In the military, the mantra is “unit cohesion, unit cohesion, unit cohesion.” In the social and business worlds, sometimes it really is whom you that counts, and how strong the bond of affinity is. The benefits of interpersonal support have been known for over a century. Charles Darwin, writing in 1871, noted that a tribe whose members were always ready to aid one another and to sacrifice themselves for the common good would be victorious over most other tribes. One of the founding fathers of the field of psychosomatic medicine was a Johns Hopkins’ trained physician by the name of Stewart Wolf. While Dr. Wolf made many important contributions, one of his greatest was his study of Roseta, Pennsylvania and is summarized in his book, “ThePower of Clan: The Influences of Human Relationships on Heart Disease.” The book told the story of the socially cohesive community of Roseta and Dr. Wolf’s amazing 25year investigation of the health of its inhabitants. What made Roseta a medical marvel was that its inhabitants possessed significant risk factors for heart disease such as smoking, high cholesterol diets, and a sedentary lifestyle. Despite these risk factors occurring at a prevalence equal to surrounding towns, the inhabitants appeared to possess an immunity to heart disease compared to their neighbors. The death rate from heart disease was less than half that of surrounding towns.

Wolf discovered that the protective factor was not in the water, nor the air, but was in the people themselves. Research revealed that social cohesiveness, traditional family values, a family-oriented social structure (where three and even four generations could reside in the same household), and emotional support imparted immunity from heart disease. The people of Roseta shared a strong Italian heritage. They practiced the same religion. They shared a strong sense of community identity and civic pride. Unfortunately, with time, the young adults embraced suburban living and with the rise of suburban living, the residents of Roseta slowly abandoned the mutually supportive family-oriented social structure and, as they did, the prevalence of heart disease ultimately rose so as to be equivalent to that of surrounding towns. The immunity that a shared identity, mutual values, and social cohesion had afforded was lost.

Having just read of the importance of interpersonal support, one must wonder what characteristics are likely to engender the support of others? We believe amongst the most compelling is integrity. Integrity is doing that which is right. It is considering not only what is good for you, but what is good for others as well. Integrity isn’t just a situationby situation process of decision-making, it is a consistent way of living. When we see it in others, we usually admire it. Integrity engenders trust. It makes us feel safe. Mahatma Gandhi was said that there are seven things that will destroy society: wealth without work; pleasure without conscience; knowledge without character; religion without sacrifice; politics without principle; science without humanity; business without ethics. Self-discipline and self-control are the hallmark characteristics of SEALs. Interestingly, compared to subsequent generations self-discipline and self-control appear to be hallmarks of the “greatest generation” as well. Self-discipline and self-control is another factor we believe engenders resilience. Perhaps the single most dangerous action one can take is the impulsive action. Road rage, airline rage, certain types of gambling, and even certain types of domestic violence may be related to the inability to practice self-control. On the other hand, we know certain health promoting behaviors, such as relaxation training, physical exercise, and practicing good nutrition require a certain self-discipline that many simply find too challenging to practice consistently. Sadly, these health promoting practices seem to engender resilience (and resistance) as we have discussed previously.

The seventh and final core characteristic of personal resilience, upon which the previous six characteristics rest, we believe is optimism and positive thinking. Optimism is the tendency to take the most positive or hopeful view of matIJEMH • Vol. 14, No. 2 • 2012 141ters. It is the tendency to expect the best outcome, and it is the belief that good prevails over evil. Optimistic people are more perseverant and resilient than are pessimists. Optimistic people tend to be more task-oriented and committed to success than are pessimistic people. Optimistic people appear to tolerate adversity to a greater extent than do pessimists. The optimist always has a reason to look forward to another day. Recent research (Everly & Firestone, in press) suggests there may be two types of optimism: passive and active. Passive optimism consists of hoping things will turn out well in the future. Active optimism is acting in a manner to increase the likelihood that things will indeed turn out well in the future. Active optimism has been described as a mandate to create a positive future.

A common characteristic of a Navy SEAL is the presence of a strong positive mental attitude which expects success. Success is a way of life for SEALs. It must be. The difference between success and failure is too often the difference between life and death. The optimistic attitude that expects, if not demands success, positively impacts upon all aspects of living. Success does not happen by chance; from the SEAL perspective, it exists because one makes it so. The optimistic expectation of success occurs, from that perspective, because of relentless preparation, understanding only too well the meaning of sacrifice. For the SEAL, success begins with an optimistic attitude. In his groundbreaking book, Learned Optimism, Dr. Martin Seligman (Seligman, 1998) argues that optimists get depressed less often, they are higher achievers, and they are physically healthier than pessimistic people. In his other book, The Optimistic Child, Dr. Seligman (Seligman, Reivich, Jaycox, & Gillham, 1995) makes the case that depression has become a virtual epidemic that has gradually increased over the years to the point that, in one research investigation, the incidence of a depressive disorder was found to be 9% in a sample of 3000 adolescent children in southeastern United States. Prior to 1960, depression was relatively rare, reported mostly by middle-aged women. Now depression appears in both males and females as early as middle school and its prevalence increases as one ages. Seligman (Seligman et al,

1995) notes, “Our society has changed from an achieving society to a feel-good society. Up until the 1960s, achievement was the most important goal to instill in our children. This goal was overtaken by the twin goals of happiness and self-esteem” (p. 40). Now you might read this and say, “What’s wrong with happiness and self-esteem?” The answer is: nothing, as long as they are built upon a foundation of something more substantial than the mere desire to possess them. Seligman argues that we cannot directly teach lasting self-esteem. Rather, he says, “self-esteem is caused by…successes and failures in the world” (p. 35).Seligman has shown that people can be taught optimistic behaviors. Dr. Albert Bandura would agree. Bandura’s (1997)work is summarized in his magnum opus on self-efficacy and human agency, entitled Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Bandura defines the perception of self-efficacy as the belief in one’s own ability to exercise control in a meaningful and positive way. More specifically, self-efficacy is the optimistic belief in one’s ability to organize and execute the courses of action required to achieve necessary and desired goals. This perception of control, or influence, Bandura points out, is an essential aspect of life itself; “People guide their livesby their beliefs of personal efficacy” (p. 3). He goes on to note: “People’s beliefs in their efficacy have diverse effects. Such beliefs influence the courses of action people choose to pursue, how much effort they put forth in given endeavors, how long they will persevere in the face of obstacles and failures…” (Bandura, 1997, p.3).Bandura has described four sources that affect the perception of self-efficacy and are particularly relevant in terms of the building of stress resilience.

They are as follows: self-efficacy by doing things successfully; self-efficacy by watching others be successful; self-efficacy through coaching, encouragement, support; and self-efficacy through self-regulation. Consistent with our previous discussions, Reivich and Shatte (2002), define resilience as the ability to “persevereand adapt when things go awry” (p. 1). Most importantly and relevant to the present discussion, they argue that resilience resides in the domain of cognitive appraisal, a theme we have discussed. Theory and controlled empirical investigations alike appear to converge on the conclusion that the response to any stressful event will be greatly influenced by the appraisal of the situation, the ability to attach a constructive meaning to the experience, the ability to foresee an effective means of coping with the challenges of a given situation, and the ability to ultimately incorporate the experience into some overarching belief system or schema (Everly, 1980; Everly & Lating, 2004; Reivich & Shatte, 2002; Smith, Davey, & Everly, 2007). A series of research studies was conducted to empirically examine the viability of the putative deterministic role of appraisal in health and work-related outcomes (Smith,

142 Everly, McCormack, Strouse

• Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient People Davey, & Everly, 1995; 2006; 2007; Smith & Everly, 1990; Smith, Everly, & Johns, 1993). In a number of investigations, acute cognitive or affective indicators were predictive of physical health outcomes as well as work-related outcomes such as job satisfaction, turnover intention, and burnout. Replicated results indicate that adverse life events are not as important in the ultimate determination of physical health, psychological health, job satisfaction, job performance, and the desire to change jobs as are the cognitive or affective indicia associated with those events (Everly, Davey, Smith, Lating, & Nucifors, 2011; Everly, Smith, & Lating, 2010). Summary The preceding impressions may be more heuristic than determinative, nevertheless they may be worthy of consideration as the immediate future does not appear to hold any “quick fix” nor spontaneous healing for a world that, at times, seems out of control. While one cannot always control the events that touch one’s life, there appears to be much one can do to withstand (resistance) or bounce back from (resilience) adversity. . The characteristics of highly resilient people appear to be more easily stated and understood than widely embraced and implemented: We believe that the defining elements of human resilience reside in seven core characteristics, all of which can be learned: 1) présence d’esprit: calm, innovative, non-dogmatic thinking, 2) acting decisively, 3) tenacity, 4) interpersonal connectedness, 5) honesty, 6) self-control, and

7) optimism and a positive perspective on life.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control.New York: Freeman. Bonnano, G.A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist,59(1), 20-28. Clausewitz, Carl Von (1976, rev.1984). On War. edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret.. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sun Tzu edited by James Clavell (1983). The art of war.Delacorte Press. Everly, G.S., Jr. (2009). The resilient child. NY: DiaMedica. Everly, G.S., Jr., (1980). Nature and treatment of the humanstress response. NY: Plenum. Everly, G.S., Jr., Strouse, DA, & Everly, GS, III (2010). Resilient Leadership. NY: DiaMedica. Everly, G.S., Jr., & Lating, J.M. (2004). Personality guidedtherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Everly, G.S., Jr., Davey, J., Smith, K, Lating, J. & Nucifora, F.

(2011). A defining aspect of human resilience in the workplace: A structural modeling analysis. Disaster Medicineand Public Health Preparedness, 5, 98-105. Everly, G.S., Jr., & Links, A. (in press). Resiliency: A Qualitative analysis of law enforcement and elite Military personnel. In Paton, D. and Violanti, J. (eds). Working inhigh risk environments: Developing sustained resiliency. Springfield, IL: CC Thomas. Everly, G.S., Jr., Smith, K, & Lating, J. (2010). Rationale for cognitively based resilience and psychological first aid (PFA) training: A structural modeling analysis. InternationalJournal of Emergency Mental Health, 11 (4),

249-262. Gladwell, M. (2000) Tipping point. NY: Little Brown Haglund, M., Cooper, N., Southwick, S., & Charney, D.

(2007). 6 keys to resilience for PTSD and everyday life. Current Psychiatry, 6, 23-30. Kaminsky, M.J., McCabe, O.L., Langlieb, A., & Everly, G.S., Jr. (2007). An evidence-informed model of human resistance, resilience, & recovery: The Johns Hopkins’outcomes-driven paradigm for disaster mental healthservices. Brief Therapy and Crisis Intervention, 7, 1-11. McCormack, D.K. (in press). Innovation: Life blood of Navy SEALs. The BLAST: Journal of Special Naval Warfare. Nucifora, F., Hall, R., & Everly, GS, Jr, (2011). Reexamining the role of the traumatic stressor and the trajectory of posttraumatic distress in thewake of disaster. DisasterMedicine and Public Health Preparedness, 5 (supplement

2): S1-4. Nucifora, F., Jr., Langlieb, A., Siegal, E., Everly, GS. Jr., & Kaminsky, M.J. (2007). Building resistance, resilience, and recovery in the wake of school and workplace violence. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness,

1 (Supplement 1), 33-37. Reivich, K., & Shatte, A. (2002). The resilience factor. NY: Broadway. IJEMH • Vol. 14, No. 2 • 2012 143Seligman, M. (1998). Learned optimism. New York, NY: Pocket Books Seligman, M.E.P., Reivich, K., Jaycox, L., & Gillham, J. (1995). The optimistic child. New York: Houghton- Mifflin. Smith, K.J., Davy, J.A., & Everly, G.S., Jr. (1995). An examination of the antecedents of job dissatisfaction and turnover intentions among CPAs in public accounting. Accounting Enquiries, 5(1), 99-142. Smith, K.J., Davy, J.A., & Everly, G.S., Jr. (2006). Stress arousal and burnout: A construct distinctiveness evaluation. Proceedings of the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association. Washington, DC. Smith, K.J., Davy, J.A., & Everly, G.S. Jr. (2007). An assessment of the contribution of stress arousal to the beyond the role stress model. Advances in Accounting BehavioralResearch, 10, 127-158..Smith, K.J., & Everly, G.S., Jr. (1990). An intra- and interoccupational analysis of stress among accounting academicians. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 2, 154 173.Smith, K., Everly, G., & Johns, A. (1993). Role of cognitiveaffective arousal in the dynamics of stressor-to-illness processes. Contemporary Accounting Research, 9, 432-449.s.William, N.R., Lindsey, E.W., Kurtz, P.D., & Jarvis, S.

(2001). From trauma to resiliency: Lessons from runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 4, 233-253.

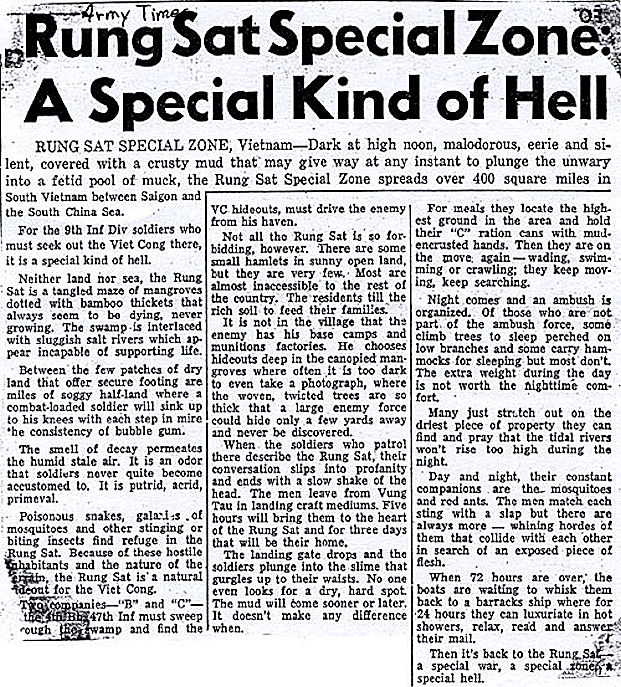

RUNG SAT SPECIAL ZONE: A SPECIAL KIND OF HELL !