The Sole Survivor Marcus Luttrell

A Navy Seal, Injured and Alone, Was Saved By Afghans’ Embrace and Comrades’ Valor

By Laura Blumenfeld Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, June 11, 2007; Page A01

The blood in his eyes almost blinded him, but the Navy Seal could hear, clattering above the trees in northeast Afghanistan, rescue helicopters.

Hey, he pleaded silently. I’m right here.

Marcus Luttrell, a fierce, 6-foot-5 rancher’s son from Texas, lay in the dirt. His face was shredded, his nose broken, three vertebrae cracked from tumbling down a ravine. A Taliban rocket-propelled grenade had ripped off his pants and riddled him with shrapnel.

As the helicopters approached, Luttrell, a petty officer first class, turned on his radio. Dirt clogged his throat, leaving him unable to speak. He could hear a pilot: “If you’re out there, show yourself.”

It was June 2005. The United States had just suffered its worst loss of life in Afghanistan since the invasion in 2001. Taliban forces had attacked Luttrell’s four-man team on a remote ridge shortly after 1 p.m. on June 28. By day’s end, 19 Americans had died. Now U.S. aircraft scoured the hills for survivors.

There would be only one. Luttrell’s ordeal — described in exclusive interviews with him and 14 men who helped save him — is among the more remarkable accounts to emerge from Afghanistan. It has been a dim and distant war, where after 5 1/2 years about 26,000 U.S. troops remain locked in conflict.

Out of that darkness comes this spark of a story. It is a tale of moral choices and of prejudices transcended. It is also a reminder of how challenging it is to be a smart soldier, and how hard it is to be a good man.

Luttrell had come to Afghanistan “to kill every SOB we could find.” Now he lay bleeding and filthy at the bottom of a gulch, unable to stand. “I could see hunks of metal and rocks sticking out of my legs,” he recalled.

He activated his emergency call beacon, which made a clicking sound. The pilots in the HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopters overhead could hear him.

“Show yourself,” one pilot urged. “We cannot stay much longer.” Their fuel was dwindling as morning light seeped into the sky, making them targets for RPGs and small-arms fire. The helicopters turned back.

As the HH-60s flew to Bagram air base, 80 miles away, one pilot told himself, “That guy’s going to die.”

Luttrell never felt so alone. His legs, numb and naked, reminded him of another loss. He had kept a magazine photograph of a World Trade Center victim in his pants pocket. Luttrell didn’t know the man but carried the picture on missions. He killed in the man’s unknown name.

Now Luttrell’s camouflage pants had been blasted off, and with them, the victim’s picture. Luttrell was feeling lightheaded. His muse for vengeance was gone.

Hunting a Taliban Leader

Luttrell’s mission had begun routinely. As darkness fell on Monday, June 27, his Seal team fast-roped from a Chinook helicopter onto a grassy ridge near the Pakistan border. They were Navy Special Operations forces, among the most elite troops in the military: Lt. Michael P. Murphy and three petty officers — Matthew G. Axelson, Danny P. Dietz and Luttrell. Their mission, code-named Operation Redwing, was to capture or kill Ahmad Shah, a Taliban leader. U.S. intelligence officials believed Shah was close to Osama bin Laden.

Luttrell, 32, is a twin. His brother was also a Seal. Each had half of a trident tattooed across his chest, so that standing together they completed the Seal symbol. They were big, visceral, horse-farm boys raised by a father Luttrell described admiringly as “a hard man.”

“He made sure we knew the world is an unforgiving, relentless place,” Luttrell said. “Anyone who thinks otherwise is totally naive.”

Luttrell, who deployed to Afghanistan in April 2005 after six years in the Navy, including two years in Iraq, welcomed the moral clarity of Kunar province. He would fight in the mountains that cradled bin Laden’s men. It was, he said, “payback time for the World Trade Center. My goal was to double the number of people they killed.”

The four Seals zigzagged all night and through the morning until they reached a wooded slope. An Afghan man wearing a turban suddenly appeared, then a farmer and a teenage boy. Luttrell gave a PowerBar to the boy while the Seals debated whether the Afghans would live or die.

If the Seals killed the unarmed civilians, they would violate military rules of engagement; if they let them go, they risked alerting the Taliban. According to Luttrell, one Seal voted to kill them, one voted to spare them and one abstained. It was up to Luttrell.

Part of his calculus was practical. “I didn’t want to go to jail.” Ultimately, the core of his decision was moral. “A frogman has two personalities. The military guy in me wanted to kill them,” he recalled. And yet: “They just seemed like — people. I’m not a murderer.”

Luttrell, by his account, voted to let the Afghans go. “Not a day goes by that I don’t think about that decision,” he said. “Not a second goes by.”

At 1:20 p.m., about an hour after the Seals released the Afghans, dozens of Taliban members overwhelmed them. The civilians he had spared, Luttrell believed, had betrayed them. At the end of a two-hour firefight, only he remained alive. He has written about it in a book going on sale tomorrow, “Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of Seal Team 10.”

Daniel Murphy, whose son Michael was killed, said he was comforted when “Mike’s admiral said, ‘Don’t think these men went down easy. There were 35 Taliban strewn on the ground.’ “

Before Murphy was shot, he radioed Bagram: “My guys are dying.”

Help came thundering over the ridgeline in a Chinook carrying 16 rescuers. But at 4:05 p.m., as the helicopter approached, the Taliban fighters fired an RPG. No one survived.

“It was deathly quiet,” Luttrell recalled. He crawled away, dragging his legs, leaving a bloody trail. The country song “American Soldier” looped through his mind. Round and round, in dizzying circles, whirled the words “I’ll bear that cross with honor.”

News of a Crash

Lone Survivor

Out of the U.S. military’s worst day of casualties in Afghanistan comes a tale of moral choices — both good and bad — and of sacrifice, comradeship, and character.

In southwestern Afghanistan, at the Kandahar air field, Maj. Jeff Peterson, 39, sat in the briefing room with his feet up on the table, watching the puppet movie “Team America: World Police.”

Peterson was a full-time Air Force reservist from lated-topics. known as Spanky because he resembles the scamp from “The Little Rascals.” He was passing a six-week stint with other reservists he called “old farts.” In three days they would head home, leaving behind the smell of burning sewage and the sound of giant camel spiders crunching mouse bones.

Someone flipped on the television news. A Chinook had crashed up north.

Peterson flew an HH-60 for the 305th Rescue Squadron. Motto: “Anytime, anywhere.” Their rescues had been minor. “An Afghani kid with a blown-up hand or a soldier with a blown-up knee,” Peterson recalled in an interview at Air Force Base.

That was okay with him. Twelve men, including Peterson’s best friend, had died during training in a midair collision in 1998. The accident, he said, “took the wind out of my life sails.” He just wanted to serve and get back to his wife, Penny, and their four small boys.

Peterson is dimply, 5 feet 8, and describes himself with a smile as “an idiot. A full-on, certified idiot.” He almost flunked out of flight school because he kept getting airsick. While the other pilots downed lasagna, he nibbled saltines. He had trouble in survival training because they had to slaughter rabbits: “I didn’t want to kill the bunny.”

Peterson dealt with stress by joking, singing “Mr. Rogers’s Neighborhood” songs on missions: It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

Now, with the news of the Chinook crash, the tension in the Kandahar briefing room amped up as a call came over the radio. Bagram needed them. Peterson grabbed his helmet and a three-day pack. He asked himself, “What is this about?”

Encounter With a Villager

The Seal wondered whether he was dying — if not from the bullet that had pierced his thigh, then surely of thirst. “I was licking sweat off my arms,” Luttrell recalled. “I tried to drink my urine.”

Crawling through the night, as Spanky Peterson’s HH-60 flew overhead with other search helicopters, he made it to a pool of water. When he lifted his head, he saw an Afghan. He reached for his rifle.

“American!” the villager said, flashing two thumbs-up. “Okay! Okay!”

“You Taliban?” Luttrell asked.

Lone Survivor

Out of the U.S. military’s worst day of casualties in Afghanistan comes a tale of moral choices — both good and bad — and of sacrifice, comradeship, and character.

The villager’s friends arrived, carrying AK-47s. They began to argue, apparently determining Luttrell’s fate. “I kept saying to myself, ‘Quit being a little bitch. Stand up and be a man.’ “

But he couldn’t stand. Three men lifted 240 pounds of dead weight and carried Luttrell to the 15-hut village of Sabray. They took his rifle.

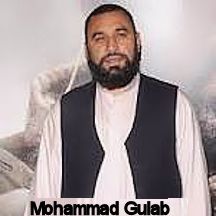

What happened next baffled him. Mohammed Gulab, 33, father of six, fed Luttrell warm goat’s milk, washed his wounds and clothed him in what Luttrell called “man jammies.”

“I didn’t trust them,” Luttrell said. “I was confused. They’d reassure me, but hell, it wasn’t in English.”

Hours after his arrival, Taliban fighters appeared and demanded that the villagers surrender the American. They threatened Gulab, Luttrell said, and tried to bribe him. “I was waiting for a good deal to come along and for Gulab to turn me over.

“I’d been in so many villages. I’d be like, ‘Up against the wall, and shut the hell up!’ So I’m like, why would these people be kind to me?” Luttrell said. “I probably killed one of their cousins. And now I’m shot up, and they’re using all the village medical supplies to help me.”

What Luttrell did not understand, he said, was that the people of Sabray were following their own rules of engagement — tribal law. Once they had carried the invalid Seal into their huts, they were committed to defend him. The Taliban fighters seemed to respect that custom, even as they lurked in the hills nearby.

During the day, children would gather around Luttrell’s cot. He touched their noses and said “nose”; the children taught him words in Pashtun. At prayer time, he kneeled as best he could, wincing from shrapnel wounds. A boy said in Arabic, “There is no god but Allah.” Marcus repeated: “La ilaha illa Allah.”

“Once you say that, you become a Muslim — you’re good to go,” he said. Luttrell offered his own unspoken prayer to Jesus: “Get me out of here.”

On several occasions, he heard helicopters. In one of them was Peterson. Come on, dude, show yourself, Peterson would silently say, looking down into the trees. At dawn, as Peterson flew back from a search, he felt his stomach sink. We failed.

On July 1, with Taliban threats intensifying, Gulab’s father, the village elder, decided to seek help at a Marine outpost five miles down in the valley. Luttrell wrote a note: “This man gave me shelter and food, and must be helped.”

=”171″>

Lone Survivor

Out of the U.S. military’s worst day of casualties in Afghanistan comes a tale of moral choices — both good and bad — and of sacrifice, comradeship, and character.

On June 28, 2005, four Navy Seals, pinned down in a firefight, radioed for help. A Chinook helicopter, carrying 16 service members, responded but was shot down. All members of the rescue team and three of four Seals on the ground died. Marcus Luttrell alone survived.

At 1 a.m. on July 2, Staff Sgt. Chris Piercecchi, 32, an Air Force pararescue jumper, picked up Gulab’s father at the Marine outpost. He flew with him to Bagram. “He was this wise, older person with a big, old beard,” Piercecchi recalled. Gulab’s father handed over Luttrell’s note and described the Seal’s trident tattoo.

U.S. commanders drew up rescue plans. “It was one of the largest combat search-and-rescue operations since Vietnam,” said Lt. Col. Steve Butow, who directed the air component from a classified location in Southwest Asia.

Planners first considered sending a Chinook to get Luttrell, while Peterson’s HH-60 would wait five miles away to evacuate casualties. But the smaller HH-60, the planners concluded, could navigate the turns approaching Sabray more easily than a lumbering Chinook.

“Sixties, you got the pickup,” the mission commander said to the HH-60 pilots.

“I was like, ‘Holy cow, dude, how am I not going to screw this up?’ ” Peterson recalled. His chest felt tight. He had never flown in combat. “You want to do your mission, but once you’re out, you’re like, damn, I’d rather be watching the American puppet movie.”

At 10:05 p.m. — five nights after Luttrell’s four-man team had set out — Peterson climbed aboard with his reservist crew: a college student, a doctor, a Border Patrol pilot, a former firefighter and a hard-of-hearing Vietnam vet.

First Lt. Dave Gonzales, 41, Peterson’s copilot, recalled that he felt for his rosary beads. “If you guys are praying guys, make sure you’re praying now,” Gonzales said. Master Sgt. Josh Appel, 39, the doctor, had never asked for God’s help before. His father was Jewish, and his mother was a German Christian: “I don’t even know what god I was talking to.”

They flew for 40 minutes toward the dead-black mountains. Voices from pilots — A-10 attack jets and AC-130 gunships flying cover — droned over five frequencies. Peterson’s crew was quiet, breathing a greasy mix of JP-8 jet fuel fumes and hot rubber.

As they climbed from 1,500 to 7,000 feet, Peterson asked about the engines: “What’s my power?” In thin air, extra weight can be deadly. He didn’t want to dump fuel; they were flying over a village. But he could sense the engines straining through the vibrations in the pedals.

Peterson broke the safety wire on the fuel switch. “Sorry, guys,” he said, looking down at the roofs. He felt bad for the people below, but he needed to lighten the aircraft if he wanted to survive. Five hundred pounds of fuel gushed out. “That’s for Penny and the boys.”

Five minutes before the helicopter reached Sabray, U.S. warplanes — guided by a ground team that had hiked overland — attacked the Taliban fighters ringing the houses. “They started shwacking the bad guys,” Peterson recalled. The clouds lit up from the explosions. The radio warned, “Known enemy 100 meters south of your position.” The back of Peterson’s neck prickled.

At 11:38 p.m., they descended into the landing zone, a ledge on a terraced cliff. The rotors spun up a blinding funnel of dirt. The aircraft wobbled, drifting left toward a wall and then right toward a cliff. Piercecchi lay down, bracing for a crash. Master Sgt. Mike Cusick, 57, the flight engineer who had been a gunner in Vietnam, screamed, “Stop left! Stop right!”

“I’m going to screw up,” Peterson recalled thinking. He thought of his best friend’s wife, how she howled when he told her that her husband, a pilot, had crashed. “Don’t let this happen to Penny.”

Then, suddenly, through the brown cloud, a bush appeared. An orientation point.

Luttrell was crouching with Gulab on the ground, watching them land. The static electricity from the rotors glowed green. “That was the most nervous I’d been,” Luttrell said. “I was waiting for an RPG to blast the helicopter.”

Gulab helped Luttrell limp through the rotor wash. Piercecchi and Appel jumped out and saw two men dressed in billowing Afghan robes.

Appel trained the laser dot of his M4 on Luttrell. “Bad guys or good guys?” Appel recalled wondering. “I hope I don’t have to shoot them.”

Someone shouted: “He’s your precious cargo!”

Piercecchi performed an identity check, based on memorized data: “What’s your dog’s name?”

Luttrell: “Emma!”

Piercecchi: “Favorite superhero?”

“Spiderman!”

Piercecchi shook his hand. “Welcome home.”

Luttrell and Gulab climbed into the helicopter. During the flight, Gulab “was latched onto my knee like a 3-year-old,” Luttrell recalled. When they landed and were separated, Gulab seemed confused. He had refused money and Luttrell’s offer of his watch.

“I put my arms around his neck,” Luttrell recalled, “and said into his ear, ‘I love you, brother.’ ” He never saw Gulab again.

The Lessons

Two years have passed. Peterson, back in Tucson, realizes he may not be “a big idiot” after all. “I feel like I could do anything,” he said.

On a recent evening, he took his boys to a Cub Scout meeting. The theme: “Cub Scouts in Shining Armor.” The den leader said: “A knight of the Round Table was someone who was very noble, who stood up for the right things. Remember what it is to be a knight, okay?”

Peterson’s boys nodded, wearing Burger King crowns that Penny had spray-painted silver.

Peterson had never spoken to Luttrell, neither in the helicopter nor afterward. Last month, the Seal phoned him.

“Hey, buddy,” he said. “This is Marcus Luttrell. Thank you for pulling me off that mountain.”

Peterson whooped.

Such happy moments have been rare for Luttrell. After recuperating, he deployed to Iraq, returning home this spring. His injuries from Afghanistan still require a “narcotic regimen.” He feels tormented by the death of his Seal friends, and he avoids sleeping because they appear in his dreams, shrieking for help.

Three weeks ago, while in New York, Luttrell visited Ground Zero. On an overcast afternoon, he looked down into the pit. The World Trade Center is his touchstone as a warrior. He had linked Sept. 11 to the people of Afghanistan: “I didn’t go over there with any respect for these people.”

But the villagers of Sabray taught him something, he said.

“In the middle of everything evil, in an evil place, you can find goodness. Goodness. I’d even call it godliness,” he said.

As Luttrell talked, he walked the perimeter fence. His gait was hulking, if not menacing, his voice angry, engorged with pain. “They protected me like a child. They treated me like I was their eldest son.”

Below Luttrell in the pit, earthmovers were digging; construction workers in orange vests directed a beeping truck. Luttrell kept talking. “They brought their cousins brandishing firearms . . . .” The cranes clanked. “And they brought their uncles, to make sure no Taliban would kill me . . . “

Luttrell kept talking over the banging and the hammering of a place that would rise again.

Downed US Seals may have got too close to Bin Laden

The Sunday Times July 10, 2005 Tony Allen-Mills, Washington and Andrew North, Kabul

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article542369.ece

THE first sign of trouble was a radio message requesting immediate extraction. A four-man team of US Navy Seal commandos had run into heavy enemy fire on a remote, thickly forested trail in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan.

Trouble turned to disaster when a US special forces helicopter carrying 16 men was shot down as it landed at the scene, killing all on board. Almost two weeks later, a mission that led to the worst US combat losses in Afghanistan since the invasion in 2001 has turned into an extraordinary manhunt. It has also opened an intriguing new front in the coalition’s battle against terrorism.

The story of Operation Red Wing, a US-led search for Taliban and Al-Qaeda guerrillas in the mountain wilderness of Kunar province, contains remarkable human drama and an unresolved military mystery.

For five days amid the hostile peaks and ravines along Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan, a lone American commando eluded the guerrillas who had killed at least two of his colleagues and destroyed the Chinook helicopter.

When the unnamed Seal finally collapsed from exhaustion he was found by a friendly Afghan villager who summoned US forces. The subsequent search for his colleagues turned up two bodies and the manhunt for the fourth commando continues this weekend despite claims by Taliban guerrillas yesterday that he had been captured and beheaded.

“We killed him at 11 o’clock today; we killed him using a knife and chopped off his head,” declared Abdul Latif Hakimi, a Taliban spokesman who has made several false claims in the past.

Yet whatever the final death toll from the worst incident in the history of the Seals — the Sea Air Land Commandos — there were tantalising hints that the original mission had been far from routine.

According to former special forces officers and other military sources, the four-man Seal strike team may have come too close to one of the US-led coalition’s highest-priority targets — perhaps Mullah Muhammad Omar, the former Taliban leader, or even Osama Bin Laden, the leader of Al-Qaeda. Other military sources suggested the target was a regional Taliban commander suspected of links with Al-Qaeda.

More than 300 US troops were yesterday combing the area for signs of the missing commando and the militants who apparently used a portable rocket-propelled grenade launcher to destroy the Chinook.

Other helicopters and remotecontrolled aerial drones were flying over deep, inaccessible valleys. Rainstorms were slowing the search, and there was a danger of growing local hostility after claims that up to 25 civilians died when US aircraft bombed a compound in Kunar province last weekend.

US officials insisted the compound was used by militants and one spokesman said the attack with precision guided weapons was part of an “intelligence-driven” operation.

But Hamid Karzai, Afghanistan’s pro-US president, warned Washington that civilian casualties could erode public support for the coalition.

It was late in the evening of Tuesday, June 28, that Lieutenant Michael Murphy and the three members of his specialist team reported an encounter with the enemy.

Pentagon spokesmen said Murphy’s unit was engaged in general reconnaissance as part of a sweep through the region amid fears that the Taliban and Al-Qaeda have quietly been regrouping and are preparing for an Iraq-style insurgency.

Yet other special forces sources noted that small Seal units like Murphy’s are primarily designed for concealment and stealth, which indicated a more specific mission.

“Its insertion represented an extraordinary risk,” said the author of an influential military blog known as Wretchard. “They would be operating in an area known to be a stronghold of the Taliban, where any contact with the enemy automatically meant they would be grossly overmatched.”

Another source noted that Murphy’s unit bore all the hallmarks of a long-range sniper team sent to hunt down a particular target. US Navy Seals are trained to spend long periods operating clandestinely.

“The fact that the US did not send in several hundred troops for a sweep instead of the four-man recon team strongly suggests the team’s mission was to fix a very high target before it could flee from an airmobile assault,” Wretchard said.

Whatever the team’s real objective, it found itself trapped in heavy rain with darkness falling. Seal veterans boast that they never call for help unless absolutely desperate. Exactly what befell Murphy and his team remains unknown, but commanders at Bagram airbase near Kabul wasted no time in dispatching eight more Seals on a helicopter crewed by eight members of an elite army unit.

As it was coming in to land in the Waigal valley, near the provincial capital of Asadabad, the helicopter was struck by what officers believe was a rocket-propelled grenade fired from the cover of nearby trees.

Lieutenant-General James Conway, chief of operations at the Pentagon, described it as a “pretty lucky shot” but when communications with the Chinook were lost, commanders were taking no chances. The next wave of troops landed a safe distance away and took 24 hours to reach the site, where it was confirmed that all 16 men on the helicopter had died.

For the four Seals on the ground, a desperate battle for survival had begun. Their story may not be told in full until the fate of the fourth member of the team is clear — the one Seal who survived has been debriefed by military officers but the Pentagon has released only the barest outline of his story for fear of compromising continuing operations in the area.

From the details released, it appears that the Seals may have dumped their backpacks to move faster on steep terrain. Former special forces sources said that when facing a superior enemy, the commandos would give each other covering fire as they mounted a phased retreat.

Coalition commanders acknowledge that for all their superior weaponry and communications, US forces are at a disadvantage in fighting in the Afghan mountains.

At some point in the mountain battle, Murphy, 29, was killed. So was Petty Officer Danny Dietz, 25. But at least one of the four Seals survived.

When he was found last weekend he was several miles from the helicopter wreckage. A friendly tribal elder notified authorities that he was caring for a wounded American. The commando was airlifted to Bagram, where his injuries were said not to be life-threatening.

US officials have not yet explained how the surviving Seal might have become separated from his missing colleague. The two dead commandos were said to have been “killed in action”.

To some US military sources, the strength of the force sent into the area suggested more than a simple search for a soldier who has been missing for 11 days. The manhunt may be providing cover for what might have been the original mission — to track down an elusive “high value” target who may once again be about to slip away.

Andrew North is the BBC’s Kabul correspondent. His reports on the security situation in Afghanistan are broadcast on all BBC news programmes

A Navy SEAL’s account of survival

Marcus Luttrell explains how, injured & alone, he got through enemy’s hills

Marcus Luttrell shares the horrific moment that he “thinks about everyday” and his tale of survivor with TODAY’s Matt Lauer. CT June 12, 2007

In his new book “Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of SEAL,” former US Navy SEALs team leader Marcus Luttrell recounts his amazing journey, on a mission to capture a notorious al Qaeda suspect, from his base in Afghanistan to the Pakastani border. Here is an excerpt from the book:

To Afghanistan … in a Flying Warehouse

This was payback time for the World Trade Center. We were coming after the guys who did it. If not the actual guys, then their blood brothers, the lunatics who still wished us dead and might try it again.

Good-byes tend to be curt among Navy SEALs. A quick backslap, a friendly bear hug, no one uttering what we’re all thinking: Here we go again, guys, going to war, to another trouble spot, another half-assed enemy willing to try their luck against us…they must be out of their minds.

It’s a SEAL thing, our unspoken invincibility, the silent code of the elite warriors of the U.S. Armed Forces. Big, fast, highly trained guys, armed to the teeth, expert in unarmed combat, so stealthy no one ever hears us coming. SEALs are masters of strategy, professional marksmen with rifles, artists with machine guns, and, if necessary, pretty handy with knives. In general terms, we believe there are very few of the world’s problems we could not solve with high explosive or a well-aimed bullet.

We operate on sea, air, and land. That’s where we got our name. U.S. Navy SEALs, underwater, on the water, or out of the water. Man, we can do it all. And where we were going, it was likely to be strictly out of the water. Way out of the water. Ten thousand feet up some treeless moonscape of a mountain range in one of the loneliest and sometimes most lawless places in the world. Afghanistan.

“ ’Bye, Marcus.” “Good luck, Mikey.” “Take it easy, Matt.” “See you later, guys.” I remember it like it was yesterday, someone pulling open the door to our barracks room, the light spilling out into the warm, dark night of Bahrain, this strange desert kingdom, which is joined to Saudi Arabia by the two-mile-long King Fahd Causeway.

The six of us, dressed in our light combat gear — flat desert khakis with Oakley assault boots — stepped outside into a light, warm breeze. It was March 2005, not yet hotter than hell, like it is in summer. But still unusually warm for a group of Americans in springtime, even for a Texan like me. Bahrain stands on the 26° north line of latitude. That’s more than four hundred miles to the south of Baghdad, and that’s hot.

Our particular unit was situated on the south side of the capital city of Manama, way up in the northeast corner of the island. This meant we had to be transported right through the middle of town to the U.S. air base on Muharraq Island for all flights to and from Bahrain. We didn’t mind this, but we didn’t love it either.

That little journey, maybe five miles, took us through a city that felt much as we did. The locals didn’t love us either. There was a kind of sullen look to them, as if they were sick to death of having the American military around them. In fact, there were districts in Manama known as black flag areas, where tradesmen, shopkeepers, and private citizens hung black flags outside their properties to signify Americans are not welcome.

I guess it wasn’t quite as vicious as Juden Verboten was in Hitler’s Germany. But there are undercurrents of hatred all over the Arab world, and we knew there were many sympathizers with the Muslim extremist fanatics of the Taliban and al Qaeda. The black flags worked. We stayed well clear of those places.

Nonetheless we had to drive through the city in an unprotected vehicle over another causeway, the Sheik Hamad, named for the emir. They’re big on causeways, and I guess they will build more, since there are thirty-two other much smaller islands forming the low-lying Bahrainian archipelago, right off the Saudi western shore, in the Gulf of Iran.

Anyway, we drove on through Manama out to Muharraq, where the U.S. air base lies to the south of the main Bahrain International Airport. Awaiting us was the huge C-130 Hercules, a giant turbo-prop freighter. It’s one of the noisiest aircraft in the stratosphere, a big, echoing, steel cave specifically designed to carry heavy-duty freight — not sensitive, delicate, poetic conversationalists such as ourselves.

We loaded and stowed our essential equipment: heavy weaps (machine guns), M4 rifles, SIG-Sauer 9mm pistols, pigstickers (combat knives), ammunition belts, grenades, medical and communication gear. A couple of the guys slung up hammocks made of thick netting. The rest of us settled back into seats that were also made of netting. Business class this wasn’t. But frogs don’t travel light, and they don’t expect comfort. That’s frogmen, by the way, which we all were.

Stuck here in this flying warehouse, this utterly primitive form of passenger transportation, there was a certain amount of cheerful griping and moaning. But if the six of us were inserted into some hellhole of a battleground, soaking wet, freezing cold, wounded, trapped, outnumbered, fighting for our lives, you would not hear one solitary word of complaint. That’s the way of our brotherhood. It’s a strictly American brotherhood, mostly forged in blood. Hard-won, unbreakable. Built on a shared patriotism, shared courage, and shared trust in one another.

There is no fighting force in the world quite like us. The flight crew checked we were all strapped in, and then those thunderous Boeing engines roared. Jesus, the noise was unbelievable. I might just as well have been sitting in the gearbox. The whole aircraft shook and rumbled as we charged down the runway, taking off to the southwest, directly into the desert wind which gusted out of the mainland Arabian peninsula. There were no other passengers on board, just the flight crew and, in the rear, us, headed out to do God’s work on behalf of the U.S. government and our commander in chief, President George W. Bush. In a sense, we were all alone. As usual.

We banked out over the Gulf of Bahrain and made a long, left-hand swing onto our easterly course. It would have been a whole hell of a lot quicker to head directly northeast across the gulf. But that would have taken us over the dubious southern uplands of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and we do not do that.

Instead we stayed south, flying high over the friendly coastal deserts of the United Arab Emirates, north of the burning sands of the Rub al Khali, the Empty Quarter. Astern of us lay the fevered cauldrons of loathing in Iraq and nearby Kuwait, places where I had previously served. Below us were the more friendly, enlightened desert kingdoms of the world’s coming natural-gas capital, Qatar; the oil-sodden emirate of Abu Dhabi; the gleaming modern high-rises of Dubai; and then, farther east, the craggy coastline of Oman.

None of us were especially sad to leave Bahrain… None of us were especially sad to leave Bahrain, which was the first place in the Middle East where oil was discovered. It had its history, and we often had fun in the local markets bargaining with local merchants for everything. But we never felt at home there, and somehow as we climbed into the dark skies, we felt we were leaving behind all that was god-awful in the northern reaches of the gulf and embarking on a brand-new mission, one that we understood.

In Baghdad we were up against an enemy we often could not see and were obliged to get out there and find. And when we found him, we scarcely knew who he was — al Qaeda or Taliban, Shiite or Sunni, Iraqi or foreign, a freedom fighter for Saddam or an insurgent fighting for some kind of a different god from our own, a god who somehow sanctioned murder of innocent civilians, a god who’d effectively booted the Ten Commandments over the touchline and out of play.

They were ever present, ever dangerous, giving us a clear pattern of total confusion, if you know what I mean. Somehow, shifting positions in the big Hercules freighter, we were leaving behind a place which was systematically tearing itself apart and heading for a place full of wild mountain men who were hell-bent on tearing us apart.

Afghanistan. This was very different. Those mountains up in the northeast, the western end of the mighty range of the Hindu Kush, were the very same mountains where the Taliban had sheltered the lunatics of al Qaeda, shielded the crazed followers of Osama bin Laden while they plotted the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on 9/11.

This was where bin Laden’s fighters found a home training base. Let’s face it, al Qaeda means “the base,” and in return for the Saudi fanatic bin Laden’s money, the Taliban made it all possible. Right now these very same guys, the remnants of the Taliban and the last few tribal warriors of al Qaeda, were preparing to start over, trying to fight their way through the mountain passes, intent on setting up new training camps and military headquarters and, eventually, their own government in place of the democratically elected one.

They may not have been the precise same guys who planned 9/11. But they were most certainly their descendants, their heirs, their followers. They were part of the same crowd who knocked down the North and South towers in the Big Apple on the infamous Tuesday morning in 2001. And our coming task was to stop them, right there in those mountains, by whatever means necessary. Thus far, those mountain men had been kicking some serious ass in their skirmishes with our military. Which was more or less why the brass had sent for us. When things get very rough, they usually send for us. That’s why the navy spends years training SEAL teams in Coronado, California, and Virginia Beach. Especially for times like these, when Uncle Sam’s velvet glove makes way for the iron fist of SPECWARCOM (that’s Special Forces Command).

And that was why all of us were here. Our mission may have been strategic, it may have been secret. However, one point was crystalline clear, at least to the six SEALs in that rumbling Hercules high above the Arabian desert. This was payback time for the World Trade Center. We were coming after the guys who did it. If not the actual guys, then their blood brothers, the lunatics who still wished us dead and might try it again. Same thing, right?

https://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/19173935/